OpenClaw and the Architecture Nobody Noticed

Everyone is writing about the OpenClaw acqui-hire as an agents story. It is an agents story. But the reason OpenClaw worked has almost nothing to do with agents and almost everything to do with where the compute happened.

This week, Sam Altman announced that Peter Steinberger, creator of OpenClaw, was joining OpenAI. The open-source project would move to an independent foundation. Meta had also bid. Both reportedly offered billions.

Since then, the takes have been predictable. "The chatbot era is over." "Anthropic fumbled by sending a cease-and-desist instead of an acquisition offer." "OpenAI is pivoting to agents." All of these are true, and none of them are particularly interesting. The interesting question is one that almost nobody is asking: why did OpenClaw work in the first place?

Because the answer has very little to do with agents, and quite a lot to do with architecture.

209,000 Stars in 84 Days

The numbers are genuinely extraordinary. OpenClaw went from zero to 209,000 GitHub stars in under three months, making it the fastest-growing software repository in history. It gained 34,168 stars in a single 48-hour period at the end of January. On the all-time GitHub ranking, it now sits at number 15 overall, and among projects that actually ship executable code (not awesome-lists or interview prep repos), only React, Python, Linux, and Vue are ahead.

Peter Steinberger built the first version in approximately one hour. He described his approach as "agentic engineering," running four to ten AI agents simultaneously and racking up 6,600 commits in January alone. The codebase was, by any traditional engineering standard, rough. Cisco's security team found that 11.3% of the skill marketplace was malicious. One of OpenClaw's own maintainers warned on Discord that "if you can't understand how to run a command line, this is far too dangerous of a project for you to use safely."

And yet people couldn't install it fast enough.

So what was it about this particular project, built by a solo developer in Vienna over a weekend, vibe-coded and riddled with security holes, that generated more adoption velocity than Kubernetes, Docker, or TensorFlow ever managed?

It Ran Where You Already Were

Most AI assistants in early 2026 lived in browser tabs. You opened a URL, typed a prompt, read a response, and then went and did the actual work yourself. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Copilot: all fundamentally the same interaction pattern. You go to the AI. The AI does not come to you.

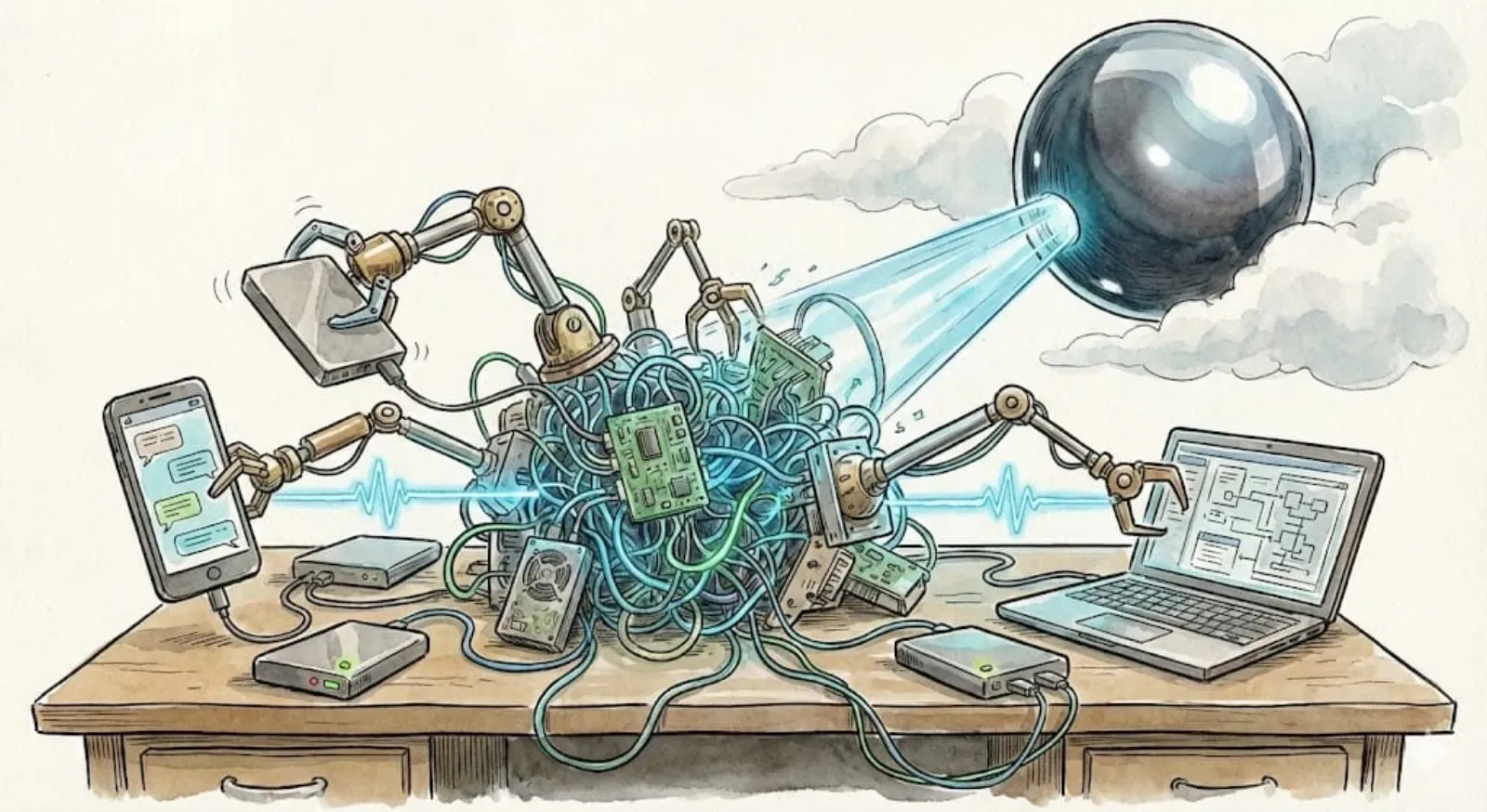

OpenClaw inverted this. It ran locally, on your own hardware (a Mac Mini, an old laptop, whatever you had), and it communicated through the messaging apps you already used: WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, Discord, Slack. You texted it the way you'd text a colleague. It didn't ask you to learn a new interface or visit a new website or authenticate against a new service. It met you where your data and your workflows already lived.

This is a product insight, obviously. But it's also an architectural one, and I think the architectural dimension is what everyone is overlooking.

When Steinberger built OpenClaw to run on user hardware and communicate through existing messaging platforms, he accidentally made three decisions that matter enormously. First, compute moved to where the data already existed (your local machine, your messaging apps, your calendar, your email). Second, no data needed to move to a centralized service for processing. Third, the "orchestration layer" was the user's own device, not a cloud platform.

This is, functionally, a compute-over-data architecture. And the fact that it emerged from a weekend hack rather than a systems design process makes it more significant, not less. It suggests that this architecture isn't just theoretically elegant; it's what users actually want when you remove the constraints of how incumbents have chosen to build things.

The Model Didn't Matter

One detail that keeps getting buried in the coverage: OpenClaw is model-agnostic. It works with Claude, GPT, DeepSeek, Llama through Ollama, and others. Steinberger told Lex Fridman that he built it originally on Claude (hence "Clawdbot"), but the architecture treats models as interchangeable inference endpoints.

This matters because it tells you where the value actually sat in the stack. It wasn't in the model. Models are increasingly commoditized; Menlo Ventures' 2025 enterprise report showed that together OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google account for 88% of enterprise LLM usage, with market share shifting dramatically year over year. OpenAI went from 50% in 2023 to 27% by end of 2025. Anthropic went from 12% to 40% in the same period. Models come and go. What doesn't change is where your data lives and how you interact with it.

The value in OpenClaw was in the deployment topology: local compute, local data access, familiar interfaces. That's the part that generated 209,000 stars. Not the model. Not the "agent" capability in the abstract. The fact that it worked here, on your machine, with your stuff.

The Centralization Paradox

And now OpenAI has acqui-hired Steinberger, and Sam Altman says he expects OpenClaw to "quickly become core to our product offerings."

Think about what that means architecturally. The thing that made OpenClaw successful was its local-first, user-controlled, decentralized deployment model. OpenAI's entire business depends on centralized inference through their API, running on their infrastructure, generating revenue per token processed through their servers.

There's a real tension here. You can't take a project whose core value proposition is "runs on your hardware, uses your messaging apps, touches your data locally" and fold it into a platform whose business model requires that inference happen centrally. You can try to build an enterprise version that preserves some of the local execution while routing inference through OpenAI's cloud, but at that point you've undermined the very thing that made it work.

Harrison Chase of LangChain noted that "the race to build the 'safe enterprise version of OpenClaw' is now the central question facing every platform vendor." But "safe enterprise version" is doing a lot of work in that sentence. If "enterprise-safe" means centralized logging, centralized inference, centralized data processing, and a SaaS billing model, then you've built a different product entirely. You've built another browser-tab assistant with better marketing.

Why This Keeps Happening

OpenClaw isn't an isolated case. The pattern keeps repeating, and the industry keeps failing to notice it.

On-device inference is growing rapidly: Apple Intelligence runs locally. Google's Gemini Nano runs on-device. Samsung's Galaxy AI processes locally. Consumers and developers consistently choose local execution when given the option, because local means faster, more private, and available offline.

Steinberger himself predicted that OpenClaw-style agents will "kill 80% of apps" because "every app is just a very slow API now." He's probably right about the disruption, but I think he's underestimating the significance of how OpenClaw does it. It doesn't just replace apps. It replaces the assumption that useful AI requires a round-trip to a data center.

Last week, I wrote about ant colonies and stigmergic coordination, arguing that the future of multi-agent systems is decentralized, environmental, and emergent rather than orchestrated from a control tower. OpenClaw, accidentally, proves the consumer side of the same thesis. The most successful agent in history didn't succeed because of a better model or a cleverer orchestration framework. It succeeded because it was local, it was distributed, and it operated in the environment where people already lived.

What Comes Next

Everyone wants to talk about the agent wars. OpenAI vs. Anthropic vs. Meta vs. Google, all racing to build the definitive agent platform. And the coverage of the OpenClaw acqui-hire frames it as another move in that chess game: OpenAI buys the agent talent, Anthropic loses because it sent lawyers instead of a term sheet, Meta picks up Manus AI as a consolation prize.

But the chess metaphor misses the point. The question isn't which company will build the best agent. The question is where agents will run. And the answer that 209,000 GitHub stars are screaming at us is: locally. On user hardware. Connected to the data and interfaces that already exist, without requiring everything to flow through a centralized cloud first.

The irony is thick. OpenAI's enterprise market share dropped from 50% to 27% in two years, largely because enterprises are diversifying away from single-vendor lock-in. The response? Acquire the one agent project that proved decentralized, local-first execution is what users actually want, and try to centralize it.

I don't know whether OpenAI will succeed in turning OpenClaw into something that fits their business model. Maybe Steinberger will push for maintaining the local-first architecture, and maybe the foundation model (in the governance sense, not the LLM sense) will preserve the project's identity. But the structural incentives point in the other direction.

What I do know is that 209,000 developers didn't star OpenClaw because they were excited about agents in the abstract. They starred it because it ran on their machine, talked to them through their messaging apps, and did useful things with their data without sending it somewhere else first. That's not an agent insight. That's an architecture insight. And it's one the industry seems determined to ignore.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!