The Natasha Problem: Why Your Data Pipeline Only Fits One Person

For most folks, you probably don’t think about clothing sizes. There’s a number, you pick it, you try on the clothes, and if they fit, then congrats, you’re that number. But how’d they pick that number? And why does every style/line/person fit slightly differently?

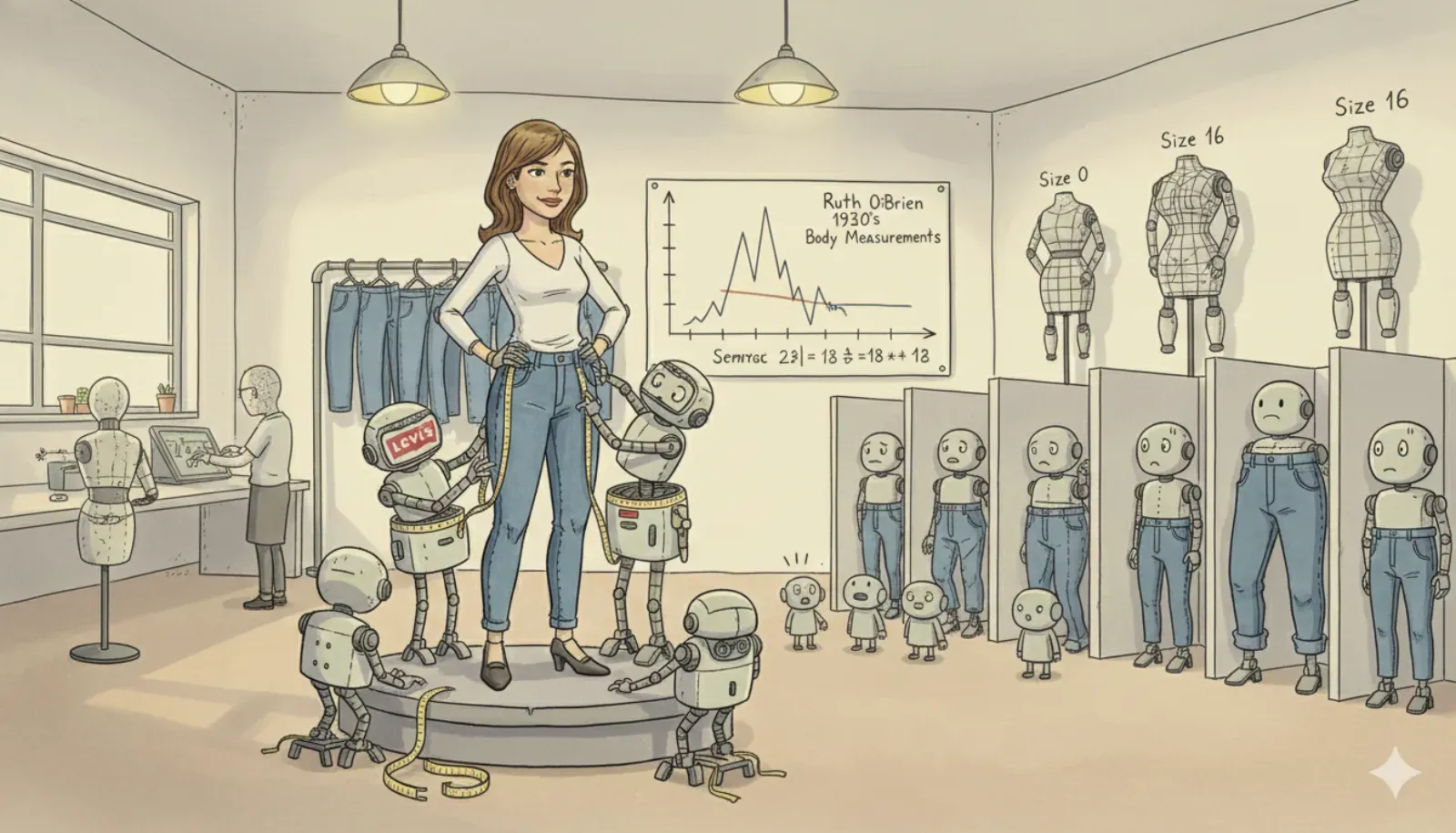

Turns out there's a woman named Natasha in Los Angeles whose body is used to design jeans for seven or eight major clothing brands. She's what the industry calls a "fit model." When Levi's or H&M or whoever designs a new pair of jeans, they don't start with measurements of the general population. They design them on a mannequin, then bring in Natasha, and adjust everything until the jeans fit her perfectly.

She's the only person in the design process with an actual human body.

Every other size is mathematical extrapolation. The size 2 isn't designed for any real person. Neither is the 4, the 8, or the 12. They're all proportional adjustments from Natasha's measurements, calculated by formula. If you're not built exactly like Natasha, your clothes don't actually fit you. They fit a mathematical projection of you derived from someone else's body.

This is, as Radiolab's Heather Radke discovered, why the dressing room feels like a personal judgment. We've internalized the idea that clothes should fit, and when they don't, we assume the problem is our body. But the clothes were never designed for our bodies. They were designed for one body, then scaled with arithmetic.

I kept thinking about this because it's exactly how we build our IT infrastructure.

The Ruth O'Brien Problem

The Natasha situation has a history. In the 1930s, a woman named Ruth O'Brien at the Bureau of Home Economics tried to solve the sizing problem scientifically. She hired "measuring squads" through the WPA to travel the country and measure women's bodies across twenty-six different dimensions: elbow to wrist, thigh girth, heel length, and on and on.

She was going to create the definitive dataset of American women's bodies.

The resulting dataset became the basis for women's clothing sizes for decades. But there never was an “average” person. It was a statistical fiction.

Your Pipeline Has a Fit Model Too

Every data pipeline has its own Natasha. Usually it's the data from headquarters, or the first customer deployment, or whatever clean dataset was available when the system was designed.

I've watched this pattern play out dozens of times. A team builds an ETL pipeline that works beautifully on their development data, where the schema is clean, the timestamps are consistent, and the sensor readings arrive in perfect intervals. They deploy to production, and 40% of their edge sites start throwing errors.

The problem isn't that the edge data is wrong. The problem is that the pipeline was designed for one shape of data, then mathematically extrapolated to handle everything else.

Consider what happens with ML training data. ImageNet became the de facto standard for computer vision benchmarks. Models trained on ImageNet achieve remarkable accuracy on ImageNet test sets. Deploy those same models to a factory floor, and they struggle with the lighting, the angles, the dust on camera lenses, the specific way that this particular production line differs from the curated images in the training set.

The model was fit to ImageNet. Everything else is extrapolation.

Or look at timestamp handling. A pipeline designed on data from a single timezone assumes UTC normalization is someone else's problem. Works fine until you're ingesting from devices across twelve timezones, some of which handle daylight saving time transitions differently, some of which have clock drift, and one of which is running firmware from 2019 that uses a different epoch.

The pipeline wasn't wrong. It was designed for one reality and scaled mathematically to others.

The Measurement Squads Never Left

Ruth O'Brien's original sin was the belief that you could measure a population once, derive a standard, and apply it forever.

We do this constantly with data.

A team defines a schema based on current requirements. They encode assumptions about data types, nullable fields, value ranges, and relationships. Then they treat that schema as ground truth, and any data that doesn't conform is "dirty" and needs to be "cleaned."

But the data isn't dirty. The data is reality. The schema is the idealized projection that reality keeps refusing to match.

I saw a project once where the sensor format had been standardized across the organization with beautiful documentation and clear specifications. Every new deployment was supposed to conform. In practice, about 60% of edge sites had made local modifications: different firmware versions, custom calibration routines, integration with legacy equipment that predated the standard by a decade.

The central data team spent enormous effort "fixing" the non-conforming data with transformations to coerce it into the standard shape, imputation for missing fields, and interpolation for different sampling rates.

By the time the data reached the analytics layer, it had been mathematically adjusted to fit a shape it never had. The "cleaned" data was a fiction, no more real than a size 2 extrapolated from Natasha's measurements.

Bodies Resist Standardization. So Does Data.

The reality is that bodies cannot be forced into interchangeable parts. The entire apparatus of industrial manufacturing assumes standardization. You take raw materials, process them into uniform components, and assemble them into identical products. It works for cars and electronics, but it fundamentally doesn't work for human bodies.

The closer you get to where data is generated, the more specific and contextual it becomes. A sensor on a drilling rig in the Permian Basin produces readings shaped by the specific geology, equipment age, and operational patterns of that site. A sensor in the North Sea produces data shaped by entirely different conditions. Both might be "pressure readings," but they're not interchangeable.

The centralization assumption says: bring all the data to one place, normalize it, and then analyze. This works if the data is genuinely similar. It falls apart when the normalization process destroys the very information you needed.

The Dressing Room Moment

Radke describes the experience of trying on clothes that don't fit as a moment of internalized judgment. The clothes were never designed for your body, but you blame yourself anyway. The sizing system has convinced you that "normal" is a real thing, and you're the deviation.

Data teams have the same experience. The pipeline breaks on edge cases, and the team treats it as a data quality problem to be solved with more transformation logic, more coercion, more normalization, more effort to force reality into the shape the system expected.

But the pipeline was designed for one type of data. Everything else is extrapolation. When the extrapolation fails, that's information. It's telling you that your model of reality was incomplete.

The question isn't "how do we clean this data to fit our schema?" The question is "why did we assume all data would look like our development dataset?"

Martha Skidmore was the closest match to Norma out of 3,864 women, and she still wasn't Norma. She was a real person, with a real body, that happened to approximate a statistical fiction slightly better than 3,863 others.

Your edge data isn't defective. It's real. The pipeline is the fiction.