The Myth of Fungible Data

Gartner recently coined a new term: geopatriation (Gartner, 2024). They predict that 75% of European and Middle Eastern enterprises will move workloads out of global clouds and back into local or sovereign environments by 2030, up from less than 5% today.

The industry response has been predictable. Compliance teams are spinning up initiatives. Cloud providers are announcing sovereign cloud offerings. Microsoft is pledging $80 billion for AI data centers to keep processing in‑country for EU users (Microsoft Blog, 2024). Everyone is treating this as a regulatory burden to be managed.

They’re reacting to the symptom, not the disease.

The Assumption Nobody Questions

For two decades, we’ve operated under a belief so fundamental it rarely gets examined: data is fungible. A byte in Singapore is equivalent to a byte in Stuttgart. A sensor reading from a factory in Shenzhen carries the same informational weight as one from a plant in Sheffield.

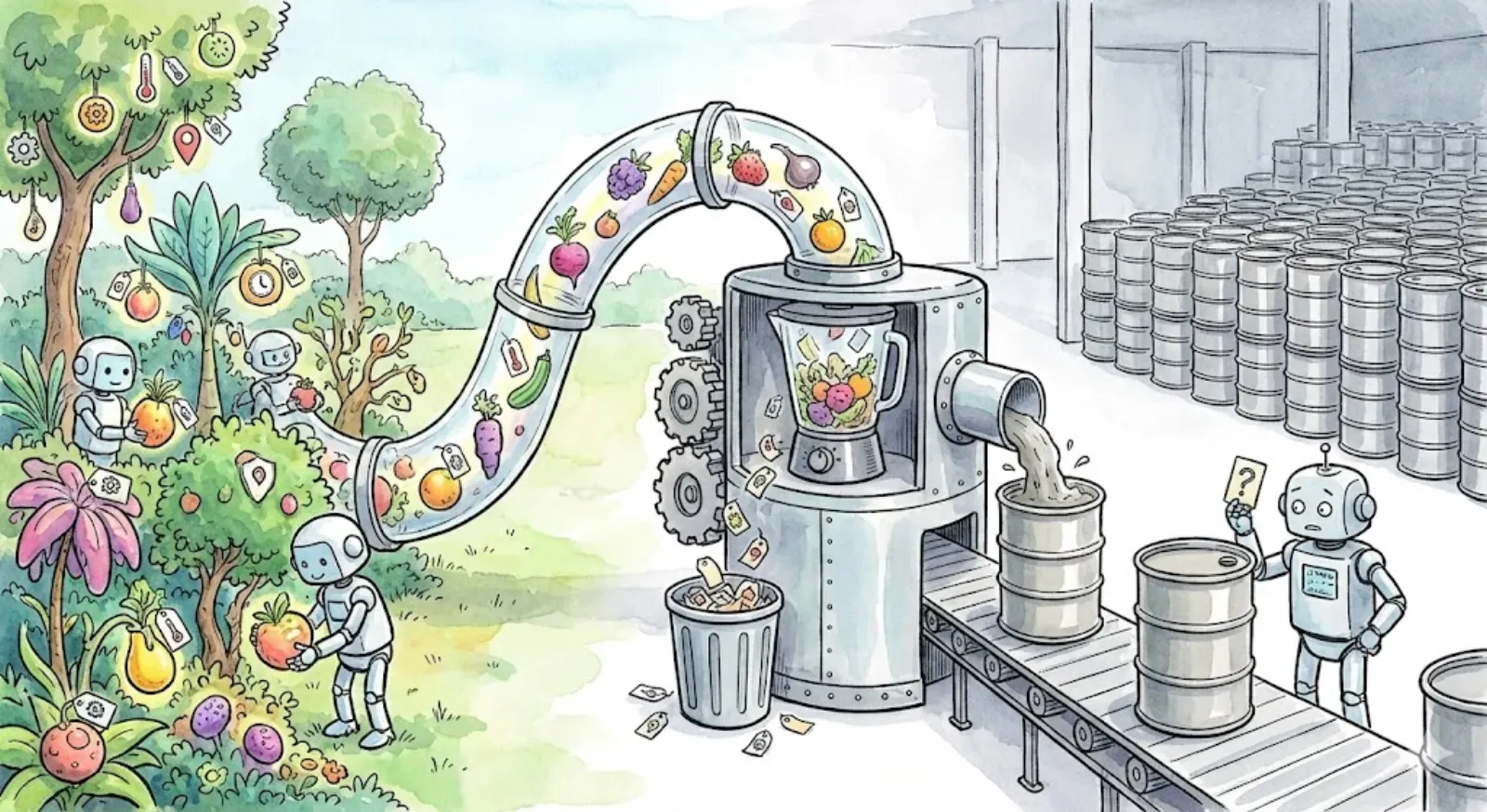

This assumption is baked into every data lake architecture, every “single source of truth” initiative, every cloud migration business case (AWS Data Lake Whitepaper). Pull all your data into a central repository, the thinking goes, and you unlock its collective value. Economies of scale. Network effects. The whole greater than the sum of its parts.

That assumption made sense when enterprise data mostly meant transactional records and documents. An invoice is an invoice. A contract is a contract.

But that’s not what enterprise data looks like anymore.

What Data Actually Is Now

Seventy‑five percent of enterprise data is now generated outside traditional data centers, largely from edge and IoT sources (IDC estimates cited in The Economist, 2023). IoT sensors, edge devices, manufacturing equipment, connected vehicles, smart infrastructure. We’re drowning in readings, measurements, and signals from more than 30 billion connected devices (Statista, 2024).

Consider a temperature sensor on a factory floor in Bavaria. It reports 32°C.

Except 32°C isn’t just a number.

It’s 32°C on a specific machine with a specific thermal history. It’s 32°C during a shift with specific operators running a specific production batch. It’s 32°C under local humidity conditions that affect what that temperature means for equipment stress. It’s 32°C calibrated against local standards and meaningful relative to that plant’s baseline.

And it’s 32°C subject to the EU Data Act, which as of September 2025 extends sovereignty and governance requirements to non‑personal industrial data (European Commission).

Strip that reading from its context and aggregate it globally, and you haven’t created insight. You’ve created noise that looks like signal.

The Thousand Shards Problem

Unfortunately, the thousand shards problem doesn’t end once data is processed locally or models are trained on intact shards. It reappears at inference, where those shards are collapsed into context‑free requests.

A predictive system trained on facility‑specific data is often invoked as if it were globally applicable. In effect, we localize data and then globalize decisions. This architectural mismatch forces models to fall back on population‑level priors learned during training—a known failure mode in deployed ML systems (Amershi et al., 2019).

IoT data exhibits systematic heterogeneity that centralized analytics can’t smooth away. Timestamp ranges vary by device. Sampling frequencies differ. Units follow local conventions. Calibration standards differ by jurisdiction.

The data exists as contextually unique shards. That meaning isn’t metadata you can attach later. It’s intrinsic to the data itself.

Why Context Isn’t Metadata

Even when enterprises preserve rich local context during data collection and model training, they routinely discard it at inference time.

Models are trained on datasets that implicitly encode geography, equipment behavior, operator practices, and environmental conditions, then deployed behind narrow APIs optimized for latency rather than understanding.

Call it metadata, lineage, or governance if you want—the problem shows up at inference, not in your catalogs.

Context that exists only during training cannot guide decisions in live systems where conditions change faster than retraining cycles—a phenomenon well documented in ML systems research (Sculley et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2021).

The industry response has been to add more metadata and lineage tracking. But inference pipelines rarely consume this information. Lineage lives in catalogs and governance tools, while inference runs on flattened inputs (Google Model Cards; NIST AI RMF).

Preserving context through inference requires more than passing richer inputs; it requires being able to prove where those inputs came from and how they were produced. Without cryptographic attestation, inference systems have no reliable way to distinguish first‑party signals from scraped text, fresh measurements from stale aggregates, or trusted transformations from opaque pipelines. This is why data provenance is becoming a runtime concern, not just a governance one. Emerging specifications like Makoto (誠) formalize this idea by introducing cryptographically signed Data Bills of Materials (DBOMs) that describe data origin, lineage, and transformation in a way inference systems can verify and reason about. This adds friction to data pipelines—but without that friction, inference systems have no defensible notion of trust.

The Illusion of Global Intelligence

Consider a predictive maintenance model trained on aggregated global data.

It produces predictions that look authoritative—and are systematically wrong in ways that are difficult to diagnose. These failures don’t look like errors; they look like variance.

This is why so many enterprise GenAI pilots fail to deliver measurable business impact (Gartner, 2024). The models are capable; the inputs they see at inference usually aren’t.

The Economic Inversion

The economics of centralization have inverted.

Compute is cheap at the edge. Data movement is expensive. Compliance costs scale with every jurisdiction crossed. One hundred thirty‑seven countries now enforce data protection or localization laws (UNCTAD).

As compute moves closer to data, it becomes cheaper to include live context at inference—if systems are designed to accept it. Many are not (IEEE Edge AI Survey).

As compute moves closer to data, a new architectural pattern emerges: compute‑over‑data pipelines that generate both results and attestations at the edge. Instead of extracting raw data into centralized systems and reconstructing meaning later, these pipelines process data in situ, producing embeddings, features, or aggregates alongside signed provenance records that travel downstream. This approach allows inference systems to incorporate not just values, but trust, scope, and freshness as first‑class inputs. Platforms like Expanso operationalize this pattern by orchestrating attested data pipelines across edge, sovereign, and cloud environments, making it possible to preserve and surface context without centralizing the raw data itself (expanso.io).

What Geopatriation Actually Reveals

Geopatriation didn’t create this problem. It exposed it.

Enterprises forced into local processing are discovering that localized systems often outperform centralized ones—not because they’re smaller, but because they preserve context.

The Path Forward

Context has a lifecycle: origin, processing, training, inference.

Break it at inference and everything upstream stops mattering.

Some data is fungible. Most operational data is not.

Seen this way, geopatriation is not merely about where data is processed, but about whether context survives the journey to inference. Attestation provides the missing connective tissue: a way to carry origin, lineage, and constraints alongside computation, regardless of where it runs. Enterprises that adopt this model won’t just comply with sovereignty requirements—they’ll unlock systems that can reason correctly about the world they operate in. The shift isn’t toward smaller or more fragmented systems, but toward systems that understand why their data exists, not just what it contains.

The data was never fungible. We only pretended it was because centralization was easier to build and because, for a long time, nobody made us pay the price.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!