The Agentic AI Infrastructure Gap: Everyone's Building Agents. Nobody's Building the Substrate.

Salesforce dropped its 2026 Connectivity Report this morning, and there's a stat in there that perfectly captures what's going wrong with enterprise AI: 50% of deployed AI agents operate in complete isolation from each other. Half. They can't share context, they can't coordinate, and the agent handling returns doesn't know what the agent managing inventory is doing three systems over.

The rest of the numbers paint a consistent picture. Organizations are running an average of 12 agents, with that number expected to climb 67% within two years. 83% of organizations say most or all teams have adopted AI agents. And yet 96% report barriers to using data for AI use cases, with 40% pointing to outdated IT architecture and disconnected systems as the primary blocker. Adoption is near-universal, and the infrastructure underneath it is fundamentally broken.

The Autonomy Illusion

The agentic AI market is projected to hit $52 billion by 2030, and Gartner says 40% of enterprise applications will embed task-specific agents by the end of this year. IBM, Deloitte, the World Economic Forum, Salesforce: everyone agrees that autonomous systems capable of planning, reasoning, and executing multi-step tasks are the future.

The problem is that "autonomous" is doing an enormous amount of work in that sentence.

Deloitte's own research found that only 14% of organizations have agentic solutions ready for deployment, and a mere 11% are running them in production. Meanwhile, 42% are still developing their strategy roadmap, and 35% have no formal strategy at all. There's a chasm between "we've adopted agents" and "our agents actually work together," and it gets wider every time someone deploys another agent into another silo.

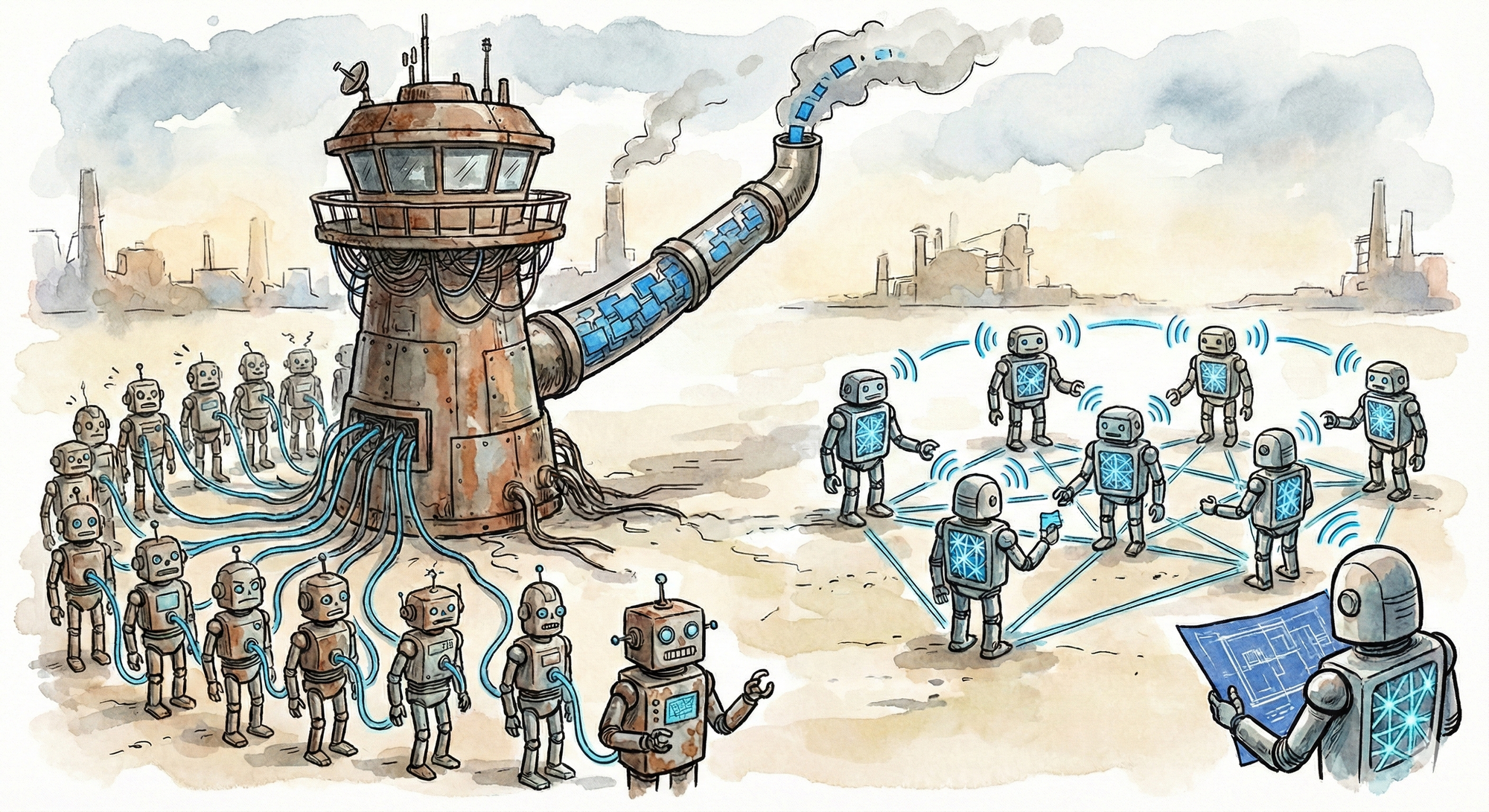

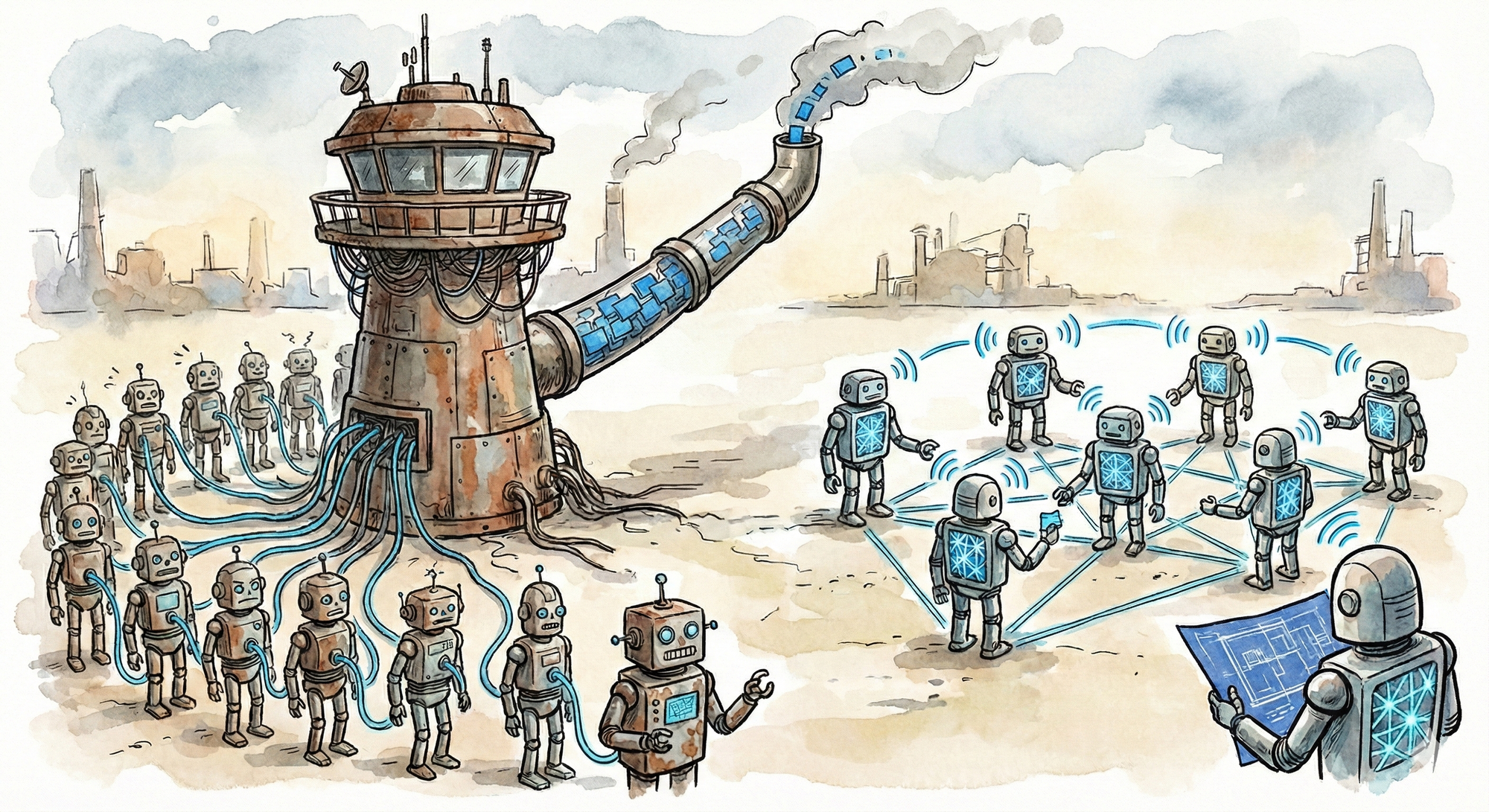

The reason is structural: we're trying to run distributed intelligence on infrastructure designed for centralized compute. The architecture doesn't fit the use case, and no amount of governance frameworks or integration middleware is going to fix that mismatch.

The API Bottleneck

A sentence from the Deloitte report that deserves more attention than it's getting:

"Most agents still rely on APIs and conventional data pipelines to access enterprise systems, which creates bottlenecks and limits their autonomous capabilities."

Think about what this actually means. We've built systems that are supposed to operate independently, make decisions, and take action, and then we've wired them to mediate every request through centralized control planes. That's like designing a self-driving car that has to radio a central dispatcher for permission at every intersection. It technically moves, but calling it "autonomous" is generous to the point of dishonesty.

The Salesforce data makes the consequences concrete: only 27% of enterprise applications are integrated, and the average enterprise runs 957 apps (up from 897 last year). The number of apps is growing, the number of agents is growing, and the connective tissue between them isn't keeping pace.

A CIO piece from January nailed the technical problem. Most enterprise APIs are built on request-response loops: client asks, server answers, connection closes. Agentic workflows don't work that way. An agent might start a task, hit a permission boundary, pivot to a different data source, circle back to the original task, and coordinate with two other agents along the way. State is everything in that environment, and if your APIs are too rigid, the agent loses the thread the moment a timeout occurs.

The industry's proposed solution? More APIs, more integration platforms, more centralized orchestration layers. Salesforce is pushing MuleSoft as the "connective tissue," and everyone else is pushing their own version of the same idea: a central control plane that mediates agent communication. This is treating the symptom as the cure. The bottleneck isn't insufficient integration. It's that we're funneling distributed intelligence through centralized chokepoints and calling it architecture.

The Edge Problem Nobody's Solving

You deploy an agent to handle customer support at the edge: a retail location, a manufacturing floor, a remote office. That agent needs local context (inventory levels, equipment status, employee availability), it needs to apply business logic (return policies, safety protocols, scheduling rules), it needs to take action (update systems, notify people, trigger workflows), and it needs to coordinate with other agents handling inventory, scheduling, and escalation. Now multiply that by hundreds of locations and thousands of agents, each with local context that matters and that can't always make a round-trip to the cloud.

How do these agents talk to each other? Today, they don't. They talk to a central orchestration layer, which talks to other agents on their behalf. The "autonomous" agents are actually fancy API clients calling home for every decision.

Worse, 27% of APIs are currently ungoverned, and only 54% of organizations have a centralized governance framework for their agentic capabilities. Half the agents are siloed, a quarter of the integration points are ungoverned, and the governance that does exist is centralized. You can call that a lot of things, but "architecture" isn't one of them.

The National Interest published a piece last week identifying these technical barriers directly: bandwidth limitations overwhelm network infrastructure when thousands of agents exchange information in real-time, synchronization challenges intensify as agents struggle to maintain consistent state across dynamic environments, and cascading failures threaten system stability when individual agent malfunctions propagate through interconnected networks. These aren't edge cases; they're the default behavior of multi-agent systems running on centralized infrastructure.

What MCP Got Right (And Where It Stops)

When Anthropic and the major players donated their agent infrastructure to the Linux Foundation, the industry bet on emergence over engineering: small, specialized components coordinating through shared protocols rather than one god-model doing everything.

Model Context Protocol is a genuine step forward. It standardizes how agents access tools and context, and the Salesforce report shows broad industry interest in agent communication protocols. But MCP solves the interface problem, not the infrastructure problem.

Knowing how to talk to a tool doesn't help when the tool is behind a firewall in a different region, the context you need is on a device that's intermittently connected, the agent you need to coordinate with is making its own decisions locally, or the data that informs your decision can't legally leave the jurisdiction it's in.

MCP gives agents a common language. What's missing is the distributed substrate that lets them actually use it across organizational and geographic boundaries, and the difference matters. A common language is a protocol specification. A distributed substrate is the physical and logical infrastructure that lets autonomous entities discover each other, establish trust, synchronize state, and coordinate action without routing everything through a central authority.

The analogy I keep coming back to: HTTP gave us a common language for the web, but HTTP alone didn't give us the web. You needed DNS for discovery, TCP/IP for reliable transport, CDNs for distribution, and load balancers for scale. The protocol was necessary but nowhere near sufficient. Agent infrastructure is at the "we have HTTP" stage, and the industry is acting like we're done.

The Convergence Collision

Spectro Cloud's enterprise AI trends analysis identifies four forces converging in 2026: sovereign AI, agentic AI, edge AI, and AI factories. They're right about the trends, but they don't say that these trends are on a collision course.

Sovereign AI says data and compute must stay within jurisdictional boundaries. Agentic AI says autonomous systems need to coordinate and share context to be useful. Edge AI says intelligence belongs close to data sources, not in centralized clouds. AI factories say we need industrial-scale infrastructure for training and inference.

You can't satisfy all four without fundamentally rethinking the architecture. Sovereignty conflicts with coordination, and edge conflicts with factories. Current infrastructure assumes you pick one or two; the future requires all of them simultaneously. The organizations stuck at 11% production deployment are the ones discovering that you can't bolt distributed capabilities onto centralized infrastructure after the fact.

The AI Expo happening in London this week is surfacing exactly this tension. Speaker after speaker is talking about governance frameworks and data readiness as prerequisites for the agentic enterprise, and they're right. But governance frameworks designed for centralized systems don't translate to distributed agent networks. The rules change when agents operate autonomously at the edge, and we haven't written the new rules yet.

What Distributed Agent Infrastructure Actually Requires

If you're building for a world where agents run at the edge, respect data sovereignty, coordinate with each other, and operate at enterprise scale, the requirements look nothing like "more APIs and better integration middleware."

You need local-first context, where agents make decisions based on local state without round-tripping to central systems. Context graphs that travel with the agent, not context that lives exclusively in a cloud database. When a manufacturing floor agent detects an anomaly, it needs to act on local sensor data, local maintenance history, and local safety protocols without waiting for a cloud round-trip that might take seconds it doesn't have.

You need peer coordination protocols so agents can coordinate with each other directly rather than through a central orchestrator. This is a different problem than MCP; it's about discovery, trust, and state synchronization between autonomous entities. When your inventory agent and your scheduling agent need to coordinate, they should be able to do that locally rather than both calling home and waiting for a centralized system to broker the conversation.

You need jurisdictional awareness baked into the architecture, not compliance bolted on at the end. An agent's capabilities should change based on its location, the data sovereignty requirements of its jurisdiction, and the regulatory context it operates in.

You need graceful degradation: what happens when an agent can't reach the network? The centralized model says fail. The distributed model says operate with reduced capability until connectivity returns. This requires agents that understand their own limitations and can make meaningful decisions about what to do locally versus what to defer.

And you need observable coordination. When 500 agents make 500 local decisions, someone needs to understand what happened, but not through central logging (that's the old model). You need distributed observability that respects data locality while enabling oversight. The Celonis research published this week found that 81% of executives say AI projects will fail without process visibility, yet 76% say their current processes are holding them back. Visibility in a distributed system is a structurally different problem than visibility in a centralized one.

The 11% Production Problem

Only 11% of organizations have agentic AI in production. The other 89% are stuck in pilots.

The conventional wisdom says it's governance concerns, legacy integration challenges, or organizational readiness. The Salesforce report's top three barriers confirm this framing: risk management and compliance (42%), lack of internal expertise (41%), and legacy infrastructure incompatibility (37%).

But look at those barriers through a systems lens and they all point to the same root cause. Risk management is hard because centralized governance doesn't map to distributed agents. Internal expertise is lacking because nobody has experience building distributed agent systems (the infrastructure doesn't exist yet). Legacy infrastructure is incompatible because it was designed for request-response patterns, not autonomous coordination.

The root cause is architectural. We're trying to deploy distributed intelligence on centralized infrastructure. You can build governance frameworks all day, integrate with legacy systems through APIs, and train your organization on agentic workflows. But until you have infrastructure that actually supports autonomous, distributed, coordinating agents rather than cloud-hosted agents that pretend to be autonomous, you're going to stay stuck in pilots.

86% of IT leaders surveyed by Salesforce are concerned that agents will introduce more complexity than value without proper integration, and they're right to be concerned. But "proper integration" through centralized platforms is how we got 50% of agents in silos in the first place. More of the same approach will produce more of the same result.

The Infrastructure We Actually Need

The companies that figure out distributed agent infrastructure will define the next era of enterprise AI. The ones still thinking in terms of "agents calling APIs through a central orchestration layer" will keep wondering why their pilot programs never graduate.

This isn't about building bigger agent orchestration platforms. It's about building substrate that lets agents operate autonomously, coordinate peer-to-peer, respect jurisdictional boundaries, and maintain coherent behavior across thousands of instances. The shift is analogous to what happened with computing itself: we moved from mainframes to client-server to cloud to edge, each time distributing capability further outward because the economics and physics demanded it. Agent infrastructure is about to make the same journey.

The agentic AI market is projected to grow from $7.8 billion to over $52 billion by 2030, but growth projections assume we solve the infrastructure problem. Today's Salesforce numbers tell us we haven't: twelve agents per organization, half of them siloed, 96% hitting data barriers, and adoption accelerating faster than the substrate can support it.

Everyone's building agents. Almost nobody's building the infrastructure for agents to actually work together. And until that changes, the 11% production rate isn't a deployment problem. It's the infrastructure telling us something we should probably listen to.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!