Digital Pheromones: What Ants Know About Agent Coordination That We Don't

We are overcomplicating this.

The AI industry is pouring billions into agent orchestration platforms, coordination frameworks, and centralized management layers. Every week brings a new architecture diagram with more boxes, more arrows, more middleware. And the results so far? Gartner predicts more than 40% of agentic AI projects will be canceled by 2027. 50% of enterprise AI agents operate in complete isolation. Nearly two-thirds of organizations haven't scaled past pilots.

Meanwhile, organisms with 250,000 neurons have been running the most sophisticated multi-agent coordination system on the planet for about 100 million years. No orchestrator. No message bus. No architecture diagram.

An ant colony of 500,000 individuals can solve optimization problems that challenge our best algorithms: shortest-path routing, load balancing, dynamic resource allocation, even adaptive supply chain logistics. Each individual ant has somewhere between 200,000 and 250,000 neurons. A human brain has about 85 billion. By any individual measure, an ant is not very smart. No ant knows the plan. No ant has a map. No ant is in charge.

And yet colonies exhibit what Stanford biologist Deborah Gordon calls "emergent intelligence" that is "measurable, modelable, and astonishingly effective." They wage territorial wars, build climate-controlled underground cities, run agriculture, and dynamically reallocate labor based on environmental conditions, all without a single centralized decision-maker.

Maybe the problem isn't that we need better coordination tools. Maybe it's that we're reaching for the wrong kind of coordination entirely.

Everybody Wants a Conductor

OpenAI launched Frontier on February 5th, a platform explicitly designed to "build, deploy, and manage AI agents" through centralized coordination. Kore.ai declared that "the real AI race isn't about building larger models; it's about mastering AI orchestration." Celonis released its 2026 Process Optimization Report showing that 85% of organizations want to become an "agentic enterprise" within three years, but 76% say their current processes are holding them back.

Everybody is reaching for the same metaphor: agents are musicians, and what we need is a conductor.

I wrote last week about the agentic AI infrastructure gap, using Salesforce's data showing that 50% of enterprise AI agents operate in complete isolation, with 96% of organizations hitting data barriers. The response was interesting, but one comment reframed the entire problem for me. A random account on Bluesky named Von Neely wrote:

"Maybe we can find a way to emulate digital pheromones and let it work itself out?"

That single sentence contains more architectural wisdom than most of the multi-agent whitepapers I've read this year.

What Ants Actually Do

The technical term for what ants do is stigmergy, a word coined by French biologist Pierre-Paul Grassé in 1959 to explain how termites coordinate nest construction. The concept is deceptively simple: agents coordinate not by communicating with each other, but by modifying a shared environment that other agents then respond to.

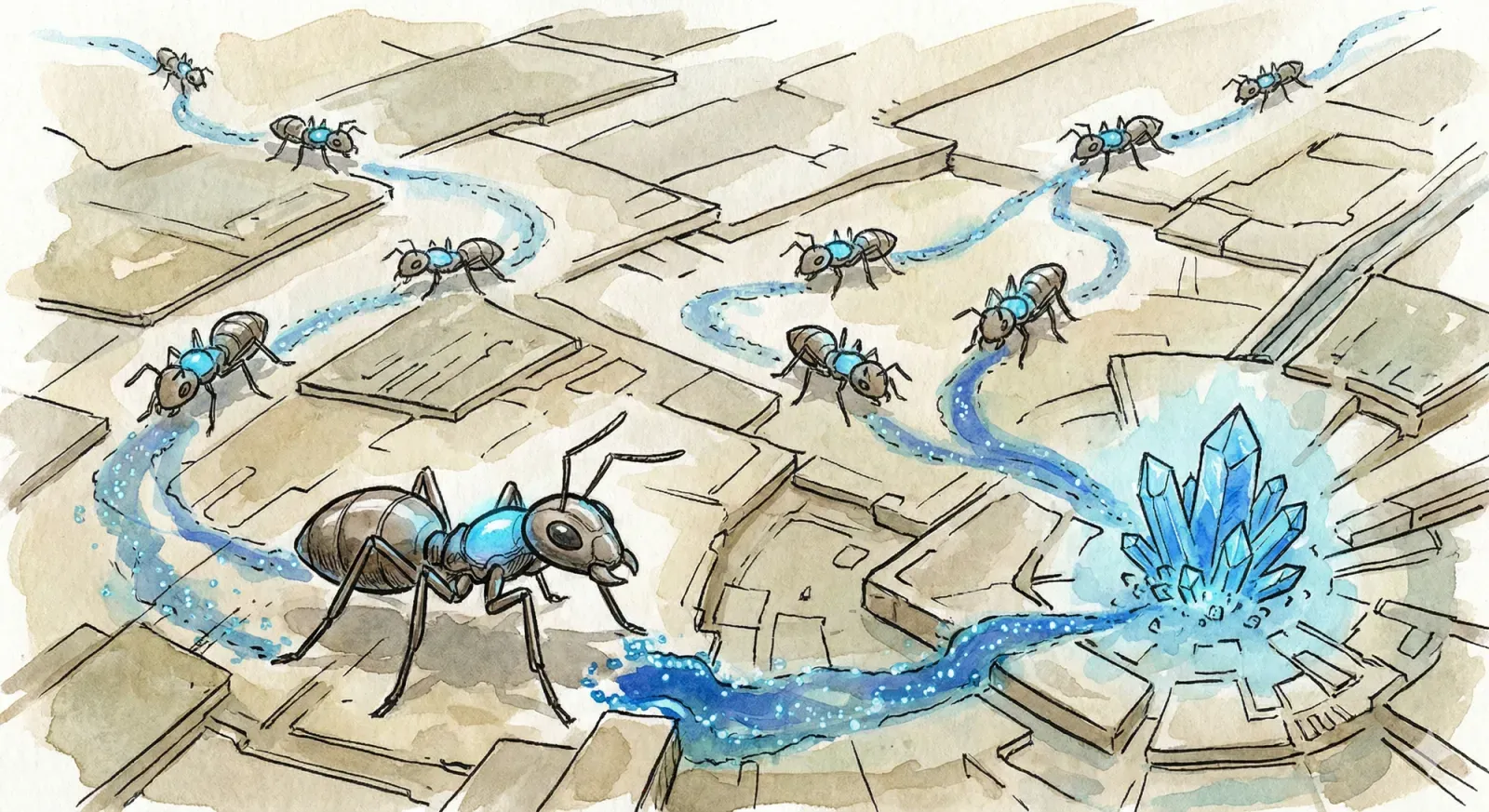

When an ant finds food, it walks back to the nest laying a chemical pheromone trail. Other ants encountering that trail are probabilistically more likely to follow it. If they also find food, they reinforce the trail on their return. Trails that lead to good food sources get reinforced, and trails that lead nowhere evaporate, because pheromones have a natural decay rate. Over time, the colony converges on optimal paths without any ant ever computing an optimal path.

Every property of this system maps to a problem we're currently struggling with in multi-agent AI, and it's worth walking through them carefully.

Start with decentralization. No coordinator, no message bus, no single point of failure. If you remove any individual ant, the colony keeps functioning. Remove half the ants, and the colony degrades gracefully and rebuilds. Try removing your orchestrator from a CrewAI or AutoGen deployment and see what happens.

Then there's the asynchronous nature of the coordination. Ants don't need to be operating at the same time. One ant lays a trail at 2pm, another picks it up at 3pm. The environment is the communication channel, and it persists between interactions. This is profoundly different from the request-response patterns that dominate current agent frameworks, where agents either talk to each other directly or go through a centralized mediator.

Pheromones also have a built-in TTL, and this is not a bug. It means stale information expires naturally. A food source that was great yesterday but is gone today stops attracting traffic without anyone needing to send an "invalidate cache" message. Compare this to the state management nightmare in most multi-agent systems, where shared context gets stale, conflicting, or just plain wrong, and nobody has a clean way to age it out.

The system self-optimizes through positive feedback loops. Good paths get reinforced, bad paths decay. The intelligence isn't in any individual component but in the interaction pattern between components and their shared environment. No one sits in a control tower analyzing telemetry and issuing new routing instructions.

And perhaps most remarkably, colonies dynamically shift labor between foraging, defense, nest maintenance, and brood care based on environmental signals. Load balancing without a load balancer. When a pheromone trail gets too crowded, ants naturally redistribute.

Context Is the Coordination Mechanism

The insight that Von Neely's comment crystallized for me is this: ants don't coordinate through communication. They coordinate through context.

No ant sends a message to another ant saying "go to the food source at coordinates (47, 83)." Instead, an ant modifies the shared environment by depositing a pheromone, and another ant responds to that modified environment by following the trail. The critical difference is where the coordination state lives. In an orchestrated system, it lives in the orchestrator. In a stigmergic system, it lives in the environment.

This matters enormously for AI agents. The dominant pattern right now is direct coordination: agents talking to other agents through message passing, function calls, or shared memory managed by a central system. Every major framework, from CrewAI to LangGraph to AutoGen, follows some version of this pattern, and every one of them hits the same scaling wall. As the number of agents grows, the coordination overhead grows faster. More agents means more messages, more state to manage, more conflicts to resolve, more failure modes to handle.

Ants solved this by making the coordination implicit rather than explicit. The pheromone trail isn't a message from Ant A to Ant B. It's a modification to the shared environment that any ant can respond to, whenever it encounters it, without needing to know who left it or why. The intelligence emerges from the aggregate behavior, not from any individual interaction.

Think about where this pattern already works in our world. Wikipedia is stigmergic: one editor modifies a page, another editor responds to the modified page, and the two never need to coordinate directly. Git commits work the same way, where you push changes to a shared repository and other developers respond to the modified codebase. Even Google's original PageRank algorithm was fundamentally stigmergic: web pages "deposited" links, and the search engine responded to the aggregate link structure. No centralized link authority told anyone where to link.

What Digital Pheromones Could Look Like

So what would stigmergic coordination look like for AI agents? Not metaphorically, but practically.

Imagine an agent processing a customer support ticket for Acme Corp. As it works, it doesn't just resolve the ticket. It leaves a contextual trace in a shared substrate: "Acme Corp, account #4471, mentioned contract renewal concerns, sentiment negative, timestamp 2026-02-13T14:30Z."

Now imagine a completely separate agent, one that handles account health analytics, running its routine analysis an hour later. It encounters that contextual trace. Nobody routed it there. No orchestrator decided these two agents should talk to each other. The analytics agent simply encountered a modification to the shared environment and adjusted its behavior, flagging the account for proactive outreach.

A third agent, one responsible for churn prediction, picks up both traces. The support interaction plus the negative account health flag combine into a signal that's stronger than either would be alone, exactly like how a reinforced pheromone trail is stronger than a single ant's deposit.

And critically, all of these traces have a decay rate. The support ticket context fades over time unless it's reinforced by additional signals. A one-off complaint doesn't permanently alter the account's profile. But a pattern of complaints, each depositing its own trace that reinforces the previous ones, creates a strong, persistent signal that naturally surfaces to any agent operating in that account's context.

The infrastructure required for this is different from what we're building today. You need a shared contextual substrate that agents can both read from and write to, with support for decay, reinforcement, and spatial locality (the digital equivalent of "nearby" pheromones being stronger). You don't need a message bus or an orchestrator. You need something more like a shared nervous system.

Why Orchestration Is the Wrong Metaphor

The numbers I cited at the top of this post aren't incidental. Everyone is diagnosing the same disease but prescribing the same medicine that isn't working.

The conductor metaphor sounds right until you think about what it actually implies. A conductor knows the entire score, can see every musician, and operates in real time, adjusting tempo and dynamics as the performance unfolds. That works for a hundred musicians in a concert hall. It does not work for thousands of autonomous agents operating across different time zones, data jurisdictions, and organizational boundaries, processing millions of interactions per day.

Orchestration works great at small scale. A handful of agents with well-defined roles, clear communication paths, and a human or system that can oversee the whole operation? Absolutely. That's the pilot stage, and it's where most organizations are today (11% in production, per Deloitte). But orchestration doesn't scale the way biology scales. You can't conduct an orchestra of 500,000 musicians, and you can't orchestrate 500,000 agents. At some point, the coordination overhead becomes the bottleneck, and you need coordination to emerge from the system rather than be imposed on it.

This is the shift that Von Neely's comment points toward: from coordination as a service provided by a central system to coordination as a property that emerges from how agents interact with a shared environment. From orchestration to stigmergy.

The Path Forward Is 100 Million Years Old

We keep trying to solve agent coordination by building better orchestrators. Ants solved it 100 million years ago by building a better environment. The substrate isn't the orchestration layer. It's the pheromone trail.

Instead of investing in increasingly complex orchestration frameworks that become the bottleneck as you scale, invest in shared contextual infrastructure that agents can deposit signals into and respond to autonomously. Build systems where coordination emerges from usage patterns rather than being dictated by a central authority. Design for decay, so stale context expires naturally. Design for reinforcement, so important signals strengthen over time. Design for locality, so agents respond most strongly to the most relevant context.

This isn't a new computer science concept. Marco Dorigo formalized ant colony optimization in 1992. Stigmergic coordination has been studied in distributed systems, robotics, and urban planning for decades. What's new is that we finally have a use case where the limitations of centralized orchestration are becoming impossible to ignore, and the properties of stigmergic coordination are exactly what we need: autonomous AI agents at enterprise scale.

The 50% of agents currently sitting in silos aren't going to be liberated by better orchestrators. They're going to be liberated by better environments.

Credit where it's due: the "digital pheromones" framing came from Von Neely on Bluesky, who dropped it in a reply to my last post. Sometimes the best architectural insights come from a random nerd who says, essentially, "why not do what ants do?" Why not indeed.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!