NVIDIA Bought the Bouncer: SchedMD and Where Lock-In Actually Lives

On December 15, 2025, NVIDIA acquired SchedMD, a 40-person company based in Lehi, Utah. The price wasn't disclosed, the press release emphasized a commitment to open source, and most coverage focused on NVIDIA’s expanding software portfolio, thereby missing the point entirely. Most folks missed how huge this was.

SchedMD maintains Slurm, the workload manager running on 65% of the TOP500 supercomputers, including more than half of the top 10 and more than half of the top 100. Every time a researcher submits a training job, every time an ML engineer queues a batch inference run, every time a national lab allocates compute for a simulation, there's a decent chance Slurm is deciding which GPUs actually run it.

Everyone's been watching the CUDA moat. Judah Taub's recent Substack piece frames it perfectly: the programming model as the source of lock-in, with five potential escape routes ranging from OpenAI's Triton to Google's TPUs to AMD's ROCm to Modular's Mojo to Tenstorrent's RISC-V approach. All of which are valid competitive threats.

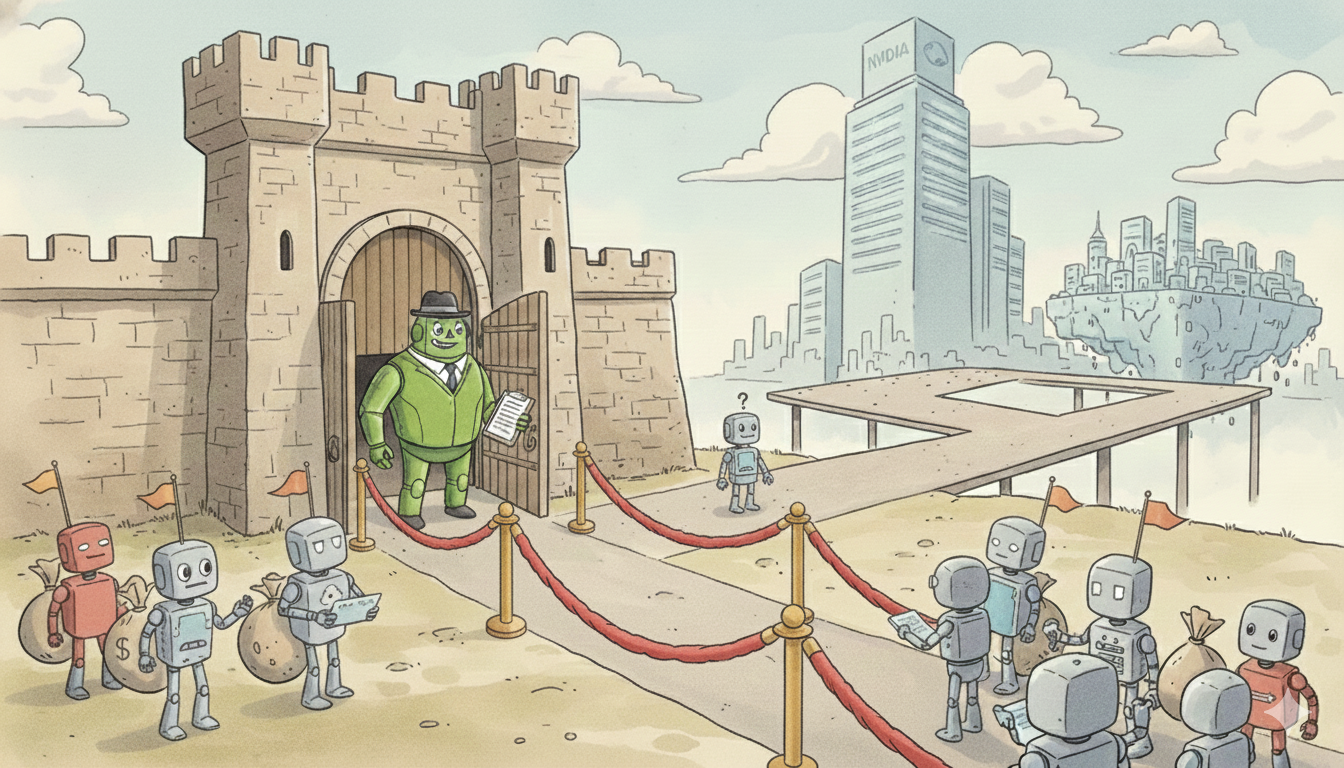

But NVIDIA, to their credit, saw through the programming model debates and identified one of the key ways to accelerate the scale-out. They bought the bouncer.

What Slurm Actually Does

If you've never submitted a job to an HPC cluster, Slurm is invisible infrastructure, and that's intentional. Researchers type sbatch my_training_job.sh and their code runs on GPUs. Still, how those GPUs get allocated, when the job actually starts, which nodes handle which portions of distributed training, how competing jobs get prioritized, whether your experiment runs tonight or next Tuesday—that's all Slurm.

The formal description sounds almost TOO basic: "allocating exclusive and/or non-exclusive access to resources, providing a framework for starting, executing, and monitoring work, and arbitrating contention for resources by managing a queue of pending jobs."

The reality is that Slurm is the layer that translates organizational policy into compute allocation. This includes things like: * Fair-share scheduling across research groups * Priority overrides for deadline-sensitive projects * Resource limits that prevent any single user from monopolizing a cluster * Preemption policies that balance throughput * Responsiveness to Hilbert curve scheduling that optimizes for network topology

And lots more. Or just launching a job without requiring SSH!

Every organization running Slurm has encoded its resource management philosophy into its configuration over years of tuning, with institutional knowledge baked into partition definitions and quality of service policies, accounting systems tied to grants and budgets, and user training built around Slurm commands. This isn't a program you swap out over a weekend.

Why Slurm Won

Slurm wasn’t the obvious choice. When development began at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 2001, the HPC world ran on proprietary schedulers: PBS (Portable Batch System) had variants everywhere, IBM's LoadLeveler dominated their ecosystem, Quadrics RMS handled specialized clusters, and Platform Computing's LSF (Load Sharing Facility) served enterprise HPC.

LLNL wanted something different because they were moving from proprietary supercomputers to commodity Linux clusters and needed a resource manager that could scale to tens of thousands of nodes, remain highly portable across architectures, and stay open source. The 2002 first release was deliberately simple, and the name originally stood for "Simple Linux Utility for Resource Management" (the acronym was later dropped, though the Futurama reference remained).

What happened next is a case study in how open source wins infrastructure markets.

PBS fragmented into OpenPBS, Torque, and PBS Pro (now Altair), with each fork diluting the community and scattering innovation, leaving organizations that chose PBS to pick which one, and none had the whole community behind them. THEN LSF went commercial when IBM acquired Platform Computing in 2012. While enterprise support is valuable, licensing costs matter when you're scaling to thousands of nodes, which makes the open-source alternative increasingly attractive. THEN Grid Engine's ownership bounced between Sun Microsystems, Oracle, and Univa, with each transition eroding community trust as development priorities shifted with corporate strategy.

Slurm stayed focused on one codebase with GPLv2 licensing that couldn't be closed and a plugin architecture that let organizations customize without forking. And in 2010, Morris Jette and Danny Auble, the lead developers, left LLNL to form SchedMD (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SchedMD), creating a commercial support model that kept the software free while funding continued development—the Red Hat playbook, applied to HPC scheduling.

Hyperion Research data from 2023 shows that 50% of HPC sites use Slurm, while the next closest, OpenPBS, sits at 18.9%, PBS Pro at 13.9%, and LSF at 10.6%. The gap isn't closing, and it's widening.

The Two-Door Strategy

In parallel with ALL that noise, NVIDIA wasn’t sitting around flat-footed.

In April 2024, NVIDIA acquired Run:ai for approximately $700 million. Run:ai builds Kubernetes-based GPU orchestration, and if Slurm is how supercomputers and traditional HPC clusters manage GPU workloads, Run:ai is how cloud-native organizations do the same thing on Kubernetes—different paradigms serving the same function, and NVIDIA now owns the scheduling layer for both.

Run:ai handles the world that emerged from containers and microservices: * Organizations running on GKE, EKS, or on-prem Kubernetes clusters * Data science teams whose workflows are built around Jupyter notebooks, Kubeflow, and MLflow * And companies that think in pods and deployments rather than batch queues and node allocations.

Slurm handles the world that emerged from supercomputing: national labs, research universities, pharmaceutical companies running molecular dynamics, financial firms running risk simulations, organizations where HPC predates the cloud, and where "scale" means dedicated clusters with thousands of nodes.

Both roads lead to GPUs, and NVIDIA now controls traffic on both.

What Lock-In Actually Looks Like

Judah Taub's CUDA analysis is correct that the programming model creates real lock-in, because rewriting GPU kernels for a different platform is expensive, and the ecosystem of libraries, tools, and community knowledge around CUDA represents decades of accumulated investment.

But programming models can be abstracted, compilers translate, and compatibility layers exist. PyTorch runs on AMD GPUs via ROCm, JAX runs on TPUs, and the code you write doesn't have to be tied permanently to CUDA, even if the transition has friction.

Orchestration creates a different kind of stickiness, because your workflows are encoded in Slurm through every batch script, every job array definition, every dependency chain that says "run step B only after step A completes successfully,” and that's not just code but institutional memory. Your accounting systems integrate with Slurm through reports that show department heads how their GPU allocation was used, chargeback systems that bill internal projects, and compliance logs that verify your government-funded research ran on approved infrastructure. Your users know Slurm through the commands they type without thinking, the debugging instincts for when jobs hang or fail, the training materials your HPC team developed, and the Stack Overflow answers they Google at 2 AM. Your cluster topology is optimized for Slurm's algorithms through a network configuration that aligns with Slurm’s understanding of a fat-tree topology, a partition structure that reflects your organizational hierarchy, and node groupings that balance locality and fairness.

Switching schedulers isn't a recompile; it's a reorganization.

The Promise and the Pattern

NVIDIA says Slurm will remain open source and vendor-neutral, and the GPLv2 license makes closing the source legally problematic anyway, so SchedMD's existing customers aren't about to get cut off.

But control of the roadmap is different from control of the code.

When NVIDIA prioritizes features, which hardware gets first-class Slurm support? When performance optimizations ship, which GPUs benefit most? When integrations between Slurm and the rest of NVIDIA’s software stack tighten, does the "vendor-neutral" promise mean equal optimization for AMD and Intel accelerators?

The pattern exists in enterprise software: Oracle doesn't prevent you from running MySQL, Microsoft doesn't prevent you from using GitHub with non-Azure clouds, but the integration points, the polish, and the performance optimizations flow toward the owner's products.

NVIDIA's official line emphasizes that Slurm "forms the essential infrastructure used by global developers, research institutions, and cloud service providers to run massive scale training infrastructure," which is true—and now NVIDIA owns that essential infrastructure.

The Distributed Gap

There's a less-discussed implication in all this.

Traditional HPC scheduling, whether Slurm or its competitors, assumes a particular architecture: a big, centralized cluster where jobs are scheduled across nodes, making the optimization problem one of matching jobs to resources within a unified system.

This architecture works well when data and compute are co-located, with training runs pulling from high-speed parallel file systems and simulations operating on datasets staged to local storage, making the cluster a world unto itself.

But increasingly, that's not the world in which organizations operate.

Data sovereignty requirements mean datasets can't always move to where the GPUs are; edge deployments generate data that shouldn’t traverse networks just to run inference; federated learning needs to coordinate training across institutions without centralizing sensitive information; and multi-cloud strategies mean compute is scattered across providers, regions, and architectures.

Run:ai helps with Kubernetes-based orchestration but assumes Kubernetes, while Slurm helps with HPC workloads but assumes a traditional cluster architecture. Neither solves the problem of "I have data in 50 locations, compute in 12 different configurations, and regulatory constraints that prevent me from pretending this is one big cluster."

NVIDIA's acquisitions reinforce the gravitational pull toward centralization: bigger clusters, more GPUs, bring your data to us. That's a valid architecture for many workloads, and for foundation model training at hyperscale, it might be the only architecture.

But it's not the only architecture that matters, and the orchestration gap for truly distributed computing remains wide open. (We have some thoughts if you’re interested :))

What NVIDIA Actually Understood

Credit where it's due: NVIDIA read the landscape correctly.

The hardware competition gets the attention, with AMD's MI300X, Intel's Gaudi, Google's TPUs, and startups raising hundreds of millions to build custom silicon, keeping everyone focused on the chip.

NVIDIA looked one layer up and recognized that whoever owns the orchestration layer owns the decision about which chips run which workloads, because the scheduler doesn't just allocate resources; it also encodes assumptions about what resources exist and how they should be used.

By acquiring both Slurm and Run:ai, NVIDIA ensures that, regardless of which paradigm you use (traditional HPC or cloud-native Kubernetes), the software layer that schedules your GPU workloads comes from NVIDIA, meaning alternatives to CUDA still need to run through NVIDIA's orchestration. It's like owning both the road and the traffic lights: the cars might be different, but they all stop at the same intersections.

Where This Leaves Everyone Else

For organizations already running Slurm, not much changes immediately because the software remains open source, SchedMD's support contracts presumably continue, and the 40 employees who built their careers around making Slurm work are now NVIDIA employees with presumably NVIDIA resources.

For organizations building alternatives to NVIDIA's hardware dominance, the landscape has grown harder: your new accelerator needs software ecosystem support, which now means either convincing NVIDIA-owned Slurm to treat your hardware as a first-class citizen or building your own orchestration layer from scratch.

For anyone thinking about distributed computing that doesn't fit the cluster model, the message is clear: the major players aren't building for you, and the orchestration layer for truly distributed, heterogeneous, data-gravity-respecting deployments doesn't exist in their portfolio.

That's both a challenge and an opportunity.

The CUDA moat is real, but it was always visible, always discussed, always the focus of competitive energy. The orchestration moat is quieter because Slurm doesn't make headlines like GPUs do, and scheduling software isn't sexy; it's just where the actual decisions get made.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!