The Solar Economics of Data

I've been obsessed with a Technology Connections video about solar panels. Not because I'm particularly passionate about energy policy (though I AM), but because he makes an argument about distributed energy that applies, almost perfectly, to distributed data.

His thesis is simple: solar beats fossil fuels on pure economics, not ideology. The math has already flipped. And the same math is flipping for data, except the case is even stronger because centralized data processing lacks the advantages that centralized power generation actually has.

The Disposable Energy Problem

Technology Connections frames fossil fuels as disposable energy. You extract them once, burn them once, and then you need more. Every megawatt-hour requires new extraction, new transportation, new combustion. The meter never stops running.

Solar panels are different. They're durable infrastructure. High capital expenditure, near-zero operating cost. Once you've paid for the panels, the fuel is free. Forever. A panel installed today will be generating electricity in 2050.

He does the math: the $19,500 spent on gasoline over a Nissan Cube's lifetime could have purchased 111 solar panels, enough for 6-7 complete home installations. Just 12 panels would cover the lifetime fuel costs of an electric vehicle in Chicago. The comparison isn't even close.

This framing, disposable versus durable, clarifies something I've been struggling to articulate about data infrastructure. We've built systems that burn resources continuously when we could have built systems that don't.

Data Movement is Burning Fuel

Think about how we process data today. You generate it at the edge: in a factory, a vehicle, a user's browser. Then you move it to a data lake. Transform it. Move it again to a warehouse. Run queries that scan terabytes. Copy subsets to analytics tools. Export results to dashboards.

Every step burns resources that never come back. Network I/O. Compute cycles. Storage duplication. Egress fees.

But the movement cost isn't even the worst part. When all that data arrives at your central infrastructure, it has to compete for the same constrained resources. A thousand queries hitting the same disk. A million requests routing through the same network pipe. Every process fighting for CPU cores, memory bandwidth, I/O channels.

Organizations now spend $931 billion annually on public cloud infrastructure, and that number is growing at 14% per year. Data integration alone is a $15.24 billion market expected to triple by 2034. We're burning fuel faster than ever, and we're burning it to feed a system that gets more expensive the more we use it.

The Central Power Plant Advantage (That Data Doesn't Have)

Technology Connections makes an important concession. Centralized power plants have a genuine advantage: they can burn fuel more efficiently than distributed alternatives. A gas turbine at a power plant converts fuel to electricity more efficiently than a backup generator in your garage. The centralization serves a purpose.

Power plants achieve this through scale. Massive turbines, optimized combustion, heat recovery systems. The infrastructure to make efficient use of fuel is expensive and complex, which justifies gathering the fuel in one place to use it.

Data processing has no such advantage.

A CPU cycle in Virginia costs the same as a CPU cycle in Tokyo. Reading from disk at the edge takes the same time as reading from disk in a data center. There's no magical efficiency you gain by moving your data to a central location before processing it. A gigabyte transformed through a few steps at the edge is equivalent to a gigabyte transformed centrally. The output is identical.

In fact, centralization makes data processing less efficient because of contention. Think about a thousand reads per second hitting a single disk. You've got one I/O channel, one controller, one set of flash cells. Every read competes with every other read. To handle that throughput, you need expensive hardware: high-end SSDs, NVMe arrays, sophisticated caching layers, careful queue management. The costs scale faster than linearly because you're fighting physics. You're forcing a thousand parallel requests through a single bottleneck.

The same principle applies everywhere in centralized infrastructure. Network access through a single pipe. Instructions competing for CPU cores. Memory bandwidth shared across processes. Everything has to be orchestrated through constrained hardware, and the cost of removing those constraints grows exponentially as you push throughput higher.

Now consider a thousand edge devices, each handling one request per second. Each device might have one-fiftieth the throughput capacity of your centralized system, but it only needs to handle one-thousandth of the load. The hardware requirements are trivial. Cooling is ambient. Disk I/O is uncontested. Memory bandwidth is abundant because nothing else is competing for it.

The per-gigabyte cost of processing at the edge is dramatically lower because you're not fighting contention. A gigabyte transformed on an edge device that's otherwise idle costs almost nothing. The same gigabyte processed centrally competes with every other gigabyte for the same constrained resources.

Where the Solar Analogy Undersells It

With power generation, the CapEx for distributed infrastructure is still substantial. Solar panels aren't free. Inverters, wiring, grid connections, maintenance. And for reliability and grid stability, you still need centralized infrastructure: transmission lines, load balancing, backup generation. The distributed generation is cheaper for fuel, but making it reliable still requires significant central investment.

Data doesn't have this constraint. You're not sacrificing reliability or consistency by doing the work where the data lives. The transformation is the same. The validation is the same. The output is the same. You're just avoiding the contention tax that comes from forcing everything through central bottlenecks.

This doesn't replace your data warehouse. You still need central infrastructure for aggregation, for cross-source analysis, for the queries that genuinely need to touch everything. But the preprocessing, the filtering, the transformation, the validation, all of that can happen at the edge where cooling is cheap, I/O is uncontested, and you're not paying exponential costs to squeeze more throughput through a single pipe.

The Movement Tax Compounds It

On top of the contention costs, you're also paying for the move itself. Egress fees represent 10-15% of total cloud costs for most organizations, and can hit 25% for data-heavy workloads. One analytics firm watched their BigQuery export costs explode from $150/month to $2,800/month in six months, about a quarter of their total cloud spend, just from moving data around.

Cross-availability-zone transfers within AWS cost $0.02 per gigabyte. Both directions get billed. Move a terabyte between zones, pay $20. Move it back, pay another $20. Do that daily and you're burning $14,600 annually just on internal shuffling, before you've processed a single record.

So you're paying twice: once for the contention at the center, and again for the privilege of moving data into that contention. The centralization tax compounds.

The Solar Farm Revelation

Technology Connections visits a solar farm and makes an observation that stuck with me: once the panels are paid for, the operation generates almost pure profit. No fuel trucks. No combustion equipment. No ongoing extraction costs. Just photons hitting silicon and money appearing in your account.

The CapEx versus OpEx distinction matters enormously. A backup generator is cheap to install but expensive to run. Grid power costs more upfront but less per unit because the utility has already paid for the generation equipment.

Solar extends this logic to its limit. Maximum CapEx, minimum OpEx. The fuel cost is zero.

Edge computing follows the same curve, but with an advantage solar doesn't have: the installed base already exists. Gartner predicted that 75% of enterprise data would be processed at the edge by 2025, up from 10% in 2018. We have billions of devices with CPUs sitting idle, like rooftops already built and waiting for solar panels. The compute capacity is deployed. We're just not using it.

And when you do use it, you're not just avoiding fuel costs. You're avoiding the contention that makes centralized processing expensive in the first place. Each edge device processes its own data without competing for shared resources. The parallelization is free.

The Materials Argument (Which Is Even Better for Data)

Technology Connections addresses the materials criticism of solar: doesn't it take energy to manufacture panels? What about rare earth minerals?

His response: batteries and panels are recyclable. The materials persist and can be reused. Burned fuel is gone forever. Every tank of gas is extracted, refined, transported, and combusted into CO2 that disperses into the atmosphere. The materials cost is paid once for solar, continuously for fossil fuels.

The data parallel is even more favorable. Computation doesn't consume anything. A CPU that processes a record at the edge is still there to process the next record. Storage is durable. The silicon persists. You're not "using up" your edge infrastructure when you run computations on it.

Contrast this with the perpetual costs of centralization. Every data movement consumes bandwidth that can't be recovered. Every redundant copy occupies storage you have to pay for continuously. Every cross-region query burns egress that directly hits your cloud bill. And every byte that arrives at the center adds to the contention that makes the next byte more expensive to process.

Distributed computation on existing infrastructure has near-zero marginal cost. Centralized data movement has a cost that scales with volume, and centralized processing has a cost that scales faster than volume because of contention.

The Economic Logic Is Inescapable

Battery storage costs have dropped to $65/MWh, making solar viable around the clock. Solar's levelized cost of energy sits at $43/MWh on average, with utility-scale projects in sunny regions hitting $37/MWh. Combined, you can get dispatchable solar for $76/MWh. Ember's analysis concluded that solar is no longer just cheap daytime electricity. It's anytime electricity.

The economic argument for centralized power generation has collapsed. Not because of environmental concerns or government mandates, but because the math changed.

The same collapse is happening with centralized data processing.

Consider: 84% of organizations cite cloud cost management as their top challenge, surpassing even security concerns. 27% of cloud spend is wasted. Companies routinely exceed their cloud budgets by 17%. Adobe reportedly overspent $80 million on cloud expenses, with data transfer charges as a major contributor.

These aren't just egress fees. They're the compounding cost of contention. Every organization hitting these walls is discovering that the architecture itself is the problem: moving everything to a central location where it fights for shared resources.

Meanwhile, edge computing is growing at 33% annually. The market will expand from $30 billion to over $500 billion in the next decade. This isn't hype. It's economic gravity. Process where the data lives, avoid the movement tax, avoid the contention tax, and the math just works.

The Ratchet Connection

In my previous post about the Brownian Ratchet for data, I argued that we need mechanisms that only capture forward progress: distributed validation that ensures data quality wherever the data lives.

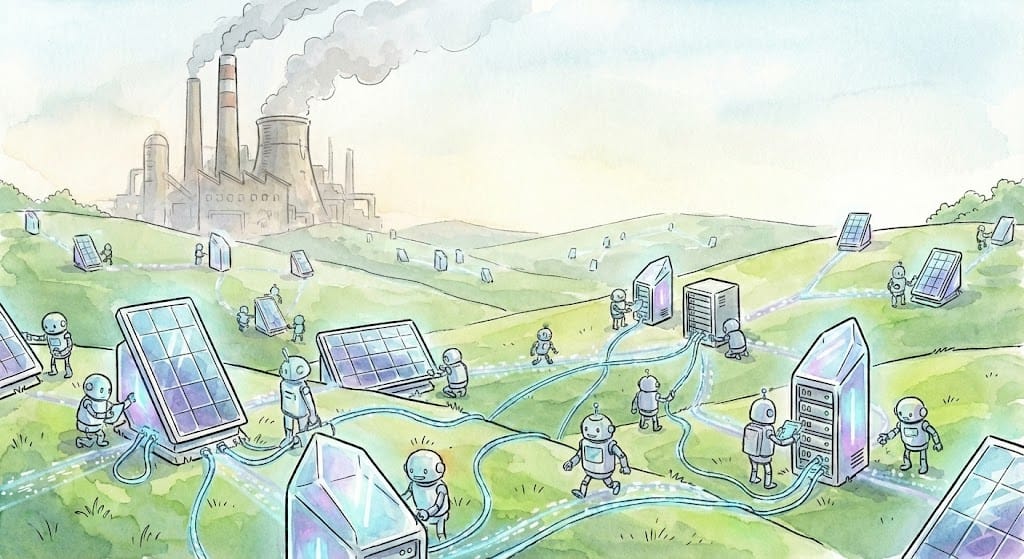

Solar farms work because they generate power in parallel, independently, without central coordination. Each panel produces what it can. The grid aggregates the results. No single point of failure. No transportation bottleneck. No contention at the generation layer.

Distributed data processing should work the same way. Validate where you generate. Process where you store. Aggregate only the results. The heavy lifting happens at the edge, where the data already lives and where resources aren't contested. Only the validated, processed results flow upstream, and those results are orders of magnitude smaller than the raw data that produced them.

This is the architectural equivalent of rooftop solar versus utility power plants. Instead of moving all your raw data to a central location (burning fuel constantly, adding to contention), you process it where it lives (harvesting idle compute, avoiding bottlenecks) and only transmit what matters.

The Midwestern Math

My dad would say "Spend more upfront if it means you never have to spend again." He'd understand the solar argument instantly. Why would you commit to buying fuel forever when you could buy panels once? The total cost of ownership isn't even close.

The same logic applies to data architecture. Why commit to paying egress fees forever when you could process data where it lives? Why pay exponentially increasing costs to handle contention at the center when you could distribute the work across devices that are sitting idle anyway?

95% of IT leaders encounter unexpected cloud storage costs. 62% exceed their cloud budgets, with unexpected egress fees as the top reason. These aren't technology problems. They're architecture problems. We've built systems that commit us to perpetual fuel costs and escalating contention when we could have built systems that don't.

Free beats expensive. Uncontested beats bottlenecked. Eventually, always.

The Transition Is Already Happening

Data infrastructure is at an inflection point. The economics of centralized processing have stopped making sense. Edge computing is growing at 33% annually because the math demands it. AI workloads are accelerating the shift because network latency and memory bandwidth trump raw compute for inference, and processing closer to the data means less contention, less movement, less waiting.

We're watching the same transition play out in data that we're watching in renewables. High upfront investment in distributed infrastructure, paid back through perpetually lower operating costs. The fuel bill drops to near zero. The contention disappears. The architecture shifts from disposable to durable.

The question isn't whether this transition will happen. The economics guarantee it. The question is whether you'll be ahead of it or behind it.

Interested in processing data where it lives? Check out Expanso. We're building intelligent data pipelines that bring compute to data instead of moving data to compute. Or don't. The economics will find you eventually.

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book about the real-world challenges of data preparation, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost concerns. I'd love to hear your thoughts!