When in Doubt, Go Up: Orbital Data Centers and the Limits of Architectural Imagination

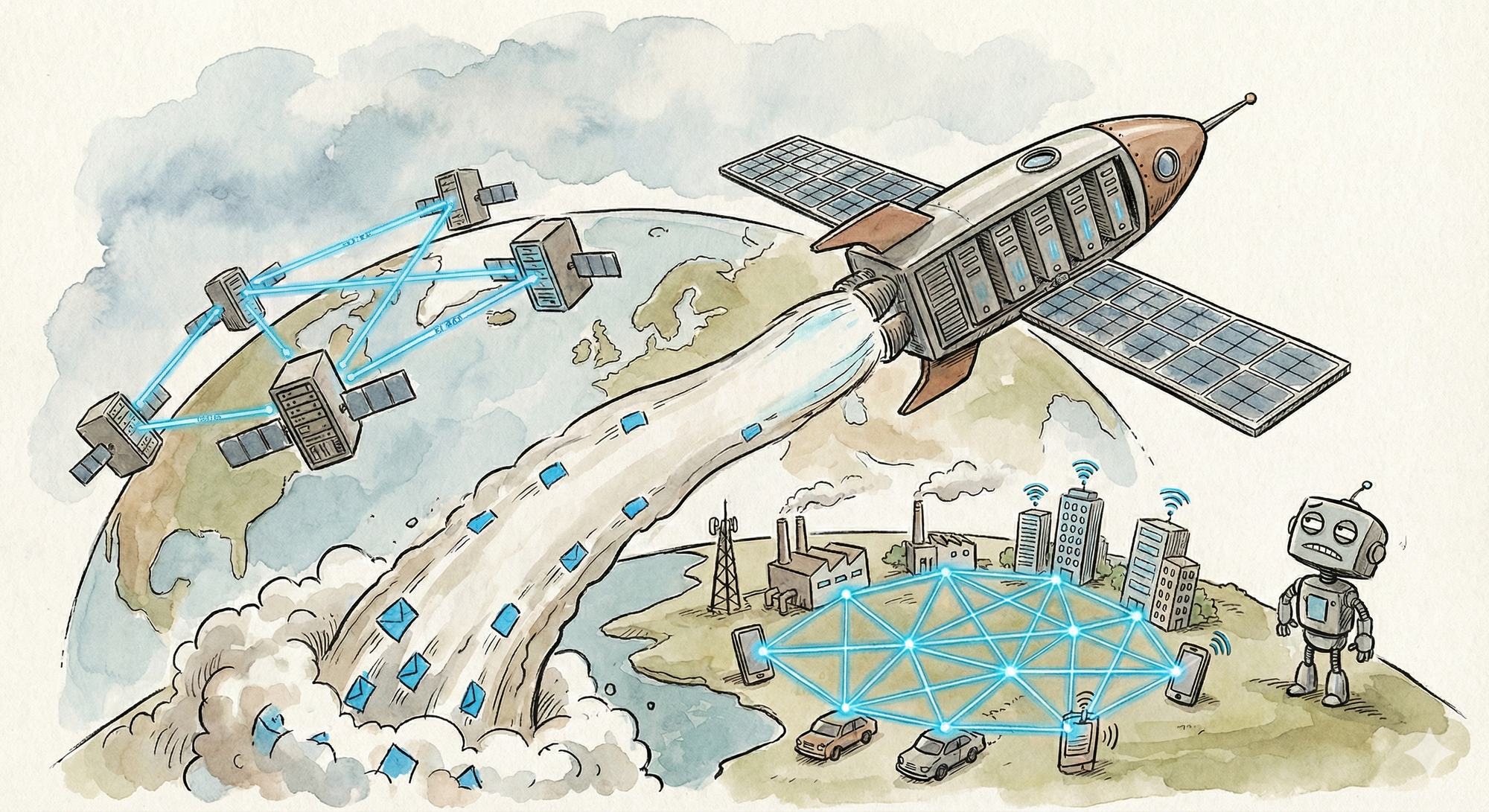

Two weeks ago, a company filed paperwork with the FCC requesting permission to launch up to one million satellites into low Earth orbit. Not communication satellites. Not GPS. Data center satellites. Solar-powered, laser-linked orbital compute nodes, designed to run AI inference workloads from space.

The filing included the phrase "first step towards becoming a Kardashev II-level civilization." That's a reference to harnessing the full power of a star. For context, we're currently a Kardashev 0.7. The filing didn't include a deployment timeline, a cost estimate, or detailed technical specifications for the satellites themselves.

I've been thinking about this filing, and what fascinates me isn't whether it's feasible. It's what it reveals about how deeply the centralization assumption has embedded itself in how we think about computing infrastructure.

The Setup

The logic goes like this: AI workloads require enormous compute. Compute requires enormous power. Power generation is constrained on Earth by grid capacity, community opposition, water availability for cooling, and the fact that there are only so many places you can build a 500-megawatt data center before the local utility starts returning your calls to voicemail. Ergo, put the data centers somewhere without these constraints. In space, solar power is nearly continuous, cooling is radiative (and free), land use is not a factor, and nobody files zoning complaints in orbit.

It's internally logical. If you accept the premise that the only variable worth optimizing is "where to put more centralized compute," then orbit is actually a reasonable answer. Maybe the best answer. And that's exactly why it's worth examining the premise.

$690 Billion and Counting

The orbital filing didn't emerge in a vacuum. It landed during the most aggressive infrastructure spending announcement in the history of technology. The five largest U.S. cloud and AI infrastructure providers have collectively committed to spending between $660 billion and $690 billion on capital expenditure in 2026, nearly doubling 2025 levels.

Amazon announced $200 billion in 2026 capex, blowing past analyst estimates. Morgan Stanley projects their free cash flow will go negative by $17 billion this year. Alphabet guided $175 to $185 billion and is raising $15 billion in high-grade bonds to fund it. Meta committed up to $135 billion, and their CFO told shareholders that the "highest order priority is investing our resources to position ourselves as a leader in AI." Barclays estimates Meta's free cash flow will drop nearly 90%.

Wall Street's response was unambiguous: the four companies lost $950 billion in combined market value in a single week. The S&P 500 went negative for 2026. A Bank of America fund manager survey found 53% now call AI stocks a bubble.

So the industry's answer to "these infrastructure costs are unsustainable" is... move the infrastructure to space?

Understand, I'm not mocking the ambition. I LOVE PEOPLE TRYING THINGS! And the engineering challenges of orbital compute are genuinely interesting, and the physics of solar power generation in LEO are real. What I'm observing is that we've arrived at a point where the most ambitious minds in technology, confronted with the escalating costs of centralized infrastructure, would rather engineer around the laws of municipal zoning than question whether centralization is the right architecture in the first place.

The Physics Problem Nobody Wants to Talk About

Let's set aside questions about launch costs, satellite reliability, radiation hardening, and space debris for a moment. Let's assume all of that gets solved. There's a more fundamental constraint that orbital data centers can't engineer around: latency.

LEO satellites operate between 500 and 2,000 kilometers above Earth. The round-trip propagation delay at those altitudes is in the range of 4-25 milliseconds just for the speed-of-light transit, before you account for routing, processing, and the fact that data has to hop through multiple laser-linked satellites before hitting a ground station. Real-world LEO broadband latency varies dramatically by geography, ranging from under 30ms in well-served regions to well over 100ms in areas with sparse ground station coverage.

For comparison, a data center in the same metro as your application serves responses in 1-5 milliseconds. A cross-continental fiber link runs 40-80ms. So orbital compute sits somewhere between "local data center" and "the other side of the planet" in latency terms, which means it's useful for batch workloads and training, but it's competing with terrestrial infrastructure that's faster for every latency-sensitive application.

Now layer on the bandwidth problem. The filing describes "high-bandwidth optical links" between satellites and to ground stations, which is real technology that works. Current inter-satellite laser links run at 200Gbps per link, with next-generation hardware targeting 1Tbps. That sounds impressive until you remember that a single modern data center interconnect runs at 400Gbps or 800Gbps per port, and a hyperscale facility might have thousands of these ports running simultaneously. The total bandwidth into and out of an orbital compute constellation is orders of magnitude less than what a terrestrial data center handles through fiber.

So orbital data centers are slower and lower-bandwidth than terrestrial ones. Their advantage is power (near-continuous solar) and cooling (radiative, free). Which means the entire value proposition rests on power being the binding constraint on AI infrastructure.

Is it?

The Constraint That Actually Binds

When 19 Michigan communities pass moratoriums on data center development, and more than 230 environmental organizations demand a national moratorium, and Senator Bernie Sanders calls for a federal halt on construction, the common diagnosis is that we have a power problem. And we do, at the point of centralized consumption.

But the power problem is a symptom, not the disease.

The disease is data movement. 75% of enterprise data is generated outside traditional data centers, at the edge: in factories, vehicles, retail locations, hospitals, mobile devices, IoT sensors. The current architecture says "move all of that data to where the compute is." That movement consumes bandwidth, incurs egress fees, introduces latency, and requires that the destination have enough power and cooling to handle the concentrated load. The power crisis at centralized facilities isn't a flaw in the model. It IS the model. When you funnel the world's data into a handful of geographic locations, those locations need ungodly amounts of electricity.

Orbital data centers don't fix this. They just move the "handful of geographic locations" to orbit. You're still moving data up to where the compute is, processing it there, and moving results back down. The data still travels. The bandwidth is still constrained. The architecture is still centralized. You've solved the power problem by accepting worse latency, worse bandwidth, and the operational complexity of maintaining infrastructure you can't physically access if something breaks.

Compare this to an alternative that nobody seems to be filing FCC applications for: processing data where it's generated.

Three Problems, Zero of Which Are Solved by Orbit

The constraints on AI infrastructure aren't just physical. They're regulatory and architectural, and the orbital proposal reveals a particular blind spot about both.

Start with regulation. Over 130 countries now have some form of data protection legislation, and the number is growing every year. Data localization laws, which require certain data to be stored and processed within national borders, grew from 67 in 2017 to 144 by 2021. The EU's GDPR doesn't mandate data residency per se, but its restrictions on cross-border transfers create a practical localization effect that most organizations satisfy by keeping EU data in EU data centers. China's Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, and PIPL mandate strict local storage for critical data categories. India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and dozens of other countries have their own versions.

Now ask yourself: whose data sovereignty laws apply in low Earth orbit?

This isn't rhetorical... it's an open legal void. The filing proposes processing AI workloads for "billions of people" on satellites that exist in no nation's jurisdiction. European health data processed in orbit isn't clearly governed by GDPR. Chinese financial data routed through a satellite at 1,200 kilometers doesn't clearly fall under the PIPL. The entire value proposition assumes that regulatory constraints on terrestrial data centers are problems to be escaped rather than requirements to be met. But those requirements exist for reasons that don't evaporate at the Kármán line, and any enterprise subject to GDPR, HIPAA, or comparable frameworks is going to need a much better answer than "the satellite was over the Atlantic at the time."

The second problem is architectural. Current AI infrastructure assumes that bigger models require bigger centralized clusters. But that assumption is being challenged from underneath by efficiency research that's decoupling model capability from hardware requirements. I wrote about DeepSeek's architectural innovations a week ago: their mHC and Engram papers demonstrate pathways where frontier-class models run on consumer hardware. V4 reportedly puts a trillion-parameter model on dual RTX 4090s through sparse mixture-of-experts and conditional memory that separates knowledge retrieval from reasoning. If the trend toward model efficiency continues, and every indication suggests it will, then the entire premise of needing orbital-scale compute starts to erode. You don't need a million satellites if a model can run on hardware that fits under a desk.

The regulatory problem and the architectural problem point in the same direction: toward processing data locally, under local jurisdiction, on increasingly capable local hardware. One is a legal requirement. The other is a technological trajectory. Neither is addressed by putting servers in space.

The Architectural Blind Spot

I wrote last month about the solar economics of data, and the core argument applies here with even more force. A CPU cycle at the edge costs the same as a CPU cycle in a data center, or in orbit, for that matter. The computation is identical. What changes is everything around the computation: the cost of getting data to the processor, the contention for shared resources, the power concentration, and the operational complexity.

When your architecture processes data where it's generated, you don't need to solve the power problem because there is no power problem. There's no concentrated demand. Each edge device uses its own power to process its own data. The load is distributed across the same infrastructure that generated the data in the first place. No community absorbs all the heat, noise, and water consumption of a 500-megawatt facility. No grid hits crisis thresholds. No senator has to file legislation because your compute is spread across millions of locations rather than concentrated in a few.

Edge computing is growing at 33% annually, from roughly $30 billion to over $500 billion in the next decade. The market is growing because the economics demand it, not because anyone filed a visionary FCC application about it. 84% of organizations cite cloud cost management as their top challenge. 27% of cloud spend is wasted. Companies routinely exceed their cloud budgets by 17%, and data transfer charges are consistently one of the top reasons.

The data gravity problem doesn't care whether your data center is in Virginia, Singapore, or low Earth orbit. If you move data to compute, you pay the movement tax. If you move compute to data, you don't.

Why We Keep Reaching for the Wrong Solution

There's something almost poetic about the progression. First we built data centers in cities. Then in rural areas with cheap land and power. Then in countries with favorable energy policies. Then underwater (Microsoft's Project Natick). Now in orbit. Each step is a creative solution to the constraints imposed by the previous step, and each step accepts the premise that centralization is non-negotiable.

I think the reason is partly economic and partly cognitive. The economic part is straightforward: hyperscalers make money by renting centralized compute. Every dollar spent on edge infrastructure is a dollar that doesn't flow through their metering systems. The incentive structure doesn't reward questioning centralization, it rewards finding new places to centralize.

The cognitive part is more interesting. Centralization feels like the natural architecture because it's what we've been building for two decades. Cloud computing was a genuine revolution in the 2000s and 2010s, and it solved real problems around capital efficiency, operational burden, and scalability. Those problems were real, and cloud was the right answer. But "cloud was the right answer in 2010" doesn't mean "cloud is the right answer for every workload in 2026," especially when the workloads have changed from serving web pages to processing sensor data, running inference at the edge, and managing AI agents that need to operate in real time on local data.

What Would a Serious Alternative Look Like

I don't want to be the person who only critiques. Orbital data centers are an impressive engineering proposal, and the people working on them are solving legitimately hard problems. The question is whether those hard problems are the right problems to solve.

If we took the same engineering ambition and pointed it at distributed infrastructure, the target list would look different. Instead of solving radiative cooling in vacuum, you'd solve efficient model distribution to heterogeneous edge hardware. Instead of laser-linked satellite mesh networking, you'd solve coordination protocols that let distributed compute nodes cooperate without centralized orchestration (something I explored through the lens of ant colonies last week). Instead of hardening silicon against radiation, you'd build fault-tolerant processing that gracefully handles the reality that edge devices are less reliable than data center servers but far more numerous and far cheaper.

These are genuinely hard engineering problems, and they're also genuinely the right problems for the architecture the world actually needs. Processing 75% of enterprise data at the edge, where it's generated, instead of hauling it to orbit or Virginia, would reduce data movement costs, reduce power concentration, and reduce latency. It would also solve the regulatory problem that orbital compute makes worse: data processed locally stays under local jurisdiction, satisfying sovereignty requirements by default rather than by legal contortion. And as models get smaller and more efficient, the hardware requirements for local processing keep dropping, turning the architectural trend into a tailwind rather than a headwind.

None of which requires a Kardashev II civilization.

The View from the Ground

When I see a filing that proposes one million satellites to solve the AI infrastructure bottleneck, I see an industry that has correctly identified three real constraints and then proposed a solution that addresses one of them, ignores another, and actively worsens the third.

The power constraint is real, and orbital solar is a legitimate approach to it. The regulatory constraint is real, and putting compute in a jurisdictional void makes it worse. The architectural constraint is real, and orbiting a million servers doubles down on the centralization model that created the problem.

The alternative isn't as cinematic. Nobody's going to file an FCC application that says "we propose to process data on the devices that already exist, in the jurisdictions where they're already located, using models that are getting efficient enough to run locally." It doesn't reference the Kardashev scale. It doesn't require a new rocket. But it solves all three constraints simultaneously: power is distributed because processing is distributed, sovereignty is satisfied because data stays local, and the architectural trend toward smaller, more efficient models means the hardware requirements keep getting easier to meet.

We've been so focused on optimizing the supply side of centralized compute, building bigger, finding more power, going to orbit, that we've barely questioned the demand side. Why does all this data need to go somewhere else to be processed? In most cases, it doesn't. We just built systems that assume it does, and now we're launching satellites to sustain that assumption.

Want to learn how intelligent data pipelines can reduce your AI costs? Check out Expanso. Or don't. Who am I to tell you what to do.*

NOTE: I'm currently writing a book based on what I have seen about the real-world challenges of data preparation for machine learning, focusing on operational, compliance, and cost. I'd love to hear your thoughts!